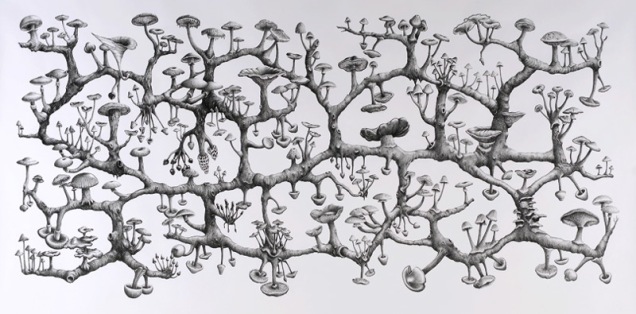

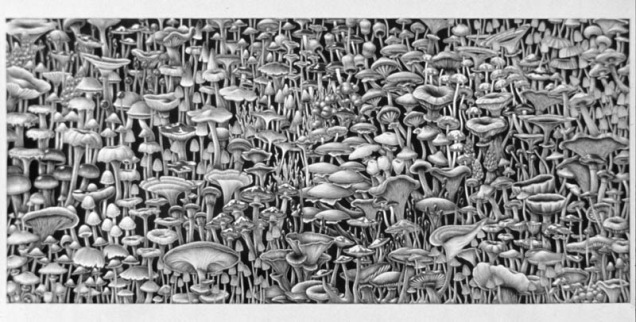

Source of image- http://www.galeriedusseldorf.com.au/GDArtists/Giblett/RG2005/source/mycelium.html (Richard Giblett)

Source of image- http://www.galeriedusseldorf.com.au/GDArtists/Giblett/RG2005/source/mycelium.html (Richard Giblett)

The idea of community as curriculum is not new. Etienne Wenger wrote about it in his 1998 book on communities of practice – and since no ideas are truly original, his thinking was probably influenced by prior writers -but nevertheless his book is the most thumbed on my bookshelf and in 1998 he wrote that education is:

‘… about balancing the production of reificative material with the design of forms of participation that provide entry into a practice and let the practice itself be its own curriculum… (p.265)

He has grounded the idea of ‘community as curriculum’ in the practice of the community, but he has also stated very clearly what he means by community and what he means by curriculum.

There is clear evidence from communities of practice that the practice itself is its own curriculum. The strongest community that I am a member of is CPsquare – the community of practice about communities of practice. This has been going for many years and has a strong group of core members who welcome peripheral participants and support them in their learning trajectory. It is a semi-open community – full access is through paid membership.

I am also a now peripheral, but originally a founding, member of the ELESIG community – a community for people interested in researching learners’ experiences of e-learning. This also has a strong core group and is an open community. This community does not yet have the depth of shared history that CPsquare does, but time will tell and it is already developing a substantial shared repertoire.

So community as curriculum is not problematic for me. I have seen it in my communities and it is evident in #rhizo14. I blogged about it early on in the course – The Community is the Curriculum in rhizo14

BUT

#rhizo14 is a course – a learning community rather than a community of practice? As Sylvia Currie (responsible for the SCoPE community – another community I am connected to) pointed out on my blog (in a comment), and I have also heard Etienne say, it doesn’t really matter what you call it, so long as the basic principles for a community and curriculum are in place.

I am, as yet, unconvinced that this can happen in ‘a course’.

What I am finding interesting to follow through in my mind, is whether it is possible to have a ‘course’ about something like rhizomatic learning/thinking without contradicting the very premise on which it stands. I have heard Stephen Downes also talk about problems with the word ‘course’ in relation to cMOOCs.

For me the most interesting curriculum topic that has arisen in the #rhizo14 ‘community’ (and I still question whether this ‘course’ qualifies as a community – but I think only time will tell) is the topography of the learning environment.

In particular I am interested in the notion of ‘ learning spaces’. Keith Hamon wrote a wonderful post on this relating it to a soccer game and field, and it relates very closely to work I have been doing with my colleague Roy Williams about the effect of the relationship between structure and openness in learning environments.

So today, I have spent some time reading around this idea of what ‘space’ means to a learner and the constraint that the idea of ‘community’ and ‘course’, if they are not carefully cultivated, might put on a learner in relation to their space for learning.

I think Ron Barnett in his book ‘A Will to Learn: Being a Student in an Age of Uncertainty‘ has summed it up for me when he writes about the tension between singularity and universality. This tension is not, I think, problematic in a network. It might be a bit more problematic in a community, but I think it is very likely to be problematic in a course.

On p.148 Barnett writes:

‘There is here a key spatial tension: to let learn, to let go, implies singularity. By this I mean that the student is to be permitted to become what she wishes, to pursue her own intellectual inclinations, to identify sets of skills that she wishes to acquire to come into her own voice. However, the teacher in higher education has a kind of tacit ethical code of ensuring that that student comes to live in keeping with the standards of her intellectual and practical fields. The student is going to be judged by those standards, in any event, but standards of this kind imply universality.’

Whilst this quote obviously applies in a situation where a student is studying for credit or some sort of certificate, I think it also says a lot about the role and power of the ‘teacher’, ‘convener’ of any course – and how that power, knowingly or unknowingly, can constrain the learner’s space.

Barnett also writes on p.148 ‘The teacher’s presence may serve perniciously to reduce the students’ space’.

This for me explains why community, course and curriculum are an uneasy fit.

Further quotes from Barnett’s book that I think are relevant to #rhizo14 are:

p.148 ‘Given spaces in which to explore and to develop, students will become differentiated from each other’.

‘Singularity is a necessary outcome of space’.

This raises for me the tension between the pressure of community, course and curriculum and the learner’s desire/need to find their own space, their own voice in relation to their own learning.

And p.149 Barnett writes:

Giving space to students, therefore, brings into play ethical dilemmas, as the singularity-universal tension itself becomes necessarily apparent.’

And so I come full circle to the question of ethics in a course, curriculum and community, which I wrote about in the very first week of #rhizo14 – Rhizomatic Learning and Ethics