In OLDaily this week, Stephen Downes, in a comment on a post by Sasha Thackaberry, makes what to me is an astute point – that the future of education is not the same thing as the future of colleges. This was the trap that the webinar hosted by Bryan Alexander, with invited speaker Cathy Davidson, fell into this week. The event was advertised as ‘reinventing education’, but for me (and I can’t find a recording of the webinar to check my perception and understanding), the discussion was more about how and what changes could be made to the existing education system (in this case the American education system).

Having followed Stephen’s e-learning 3.0 MOOC at the end of last year, I know that he has done a considerable amount of ‘out of the box’ thinking about the future of education, and has recently made at least two, that I know of, presentations about this. See:

This thinking is very much influenced by his knowledge of advancing technologies and how these might be used to ‘reinvent education’ but it is not only influenced by technology. For the e-learning 3.0 MOOC these are the questions that we discussed: I regard myself to be adequately proficient with technology, but I don’t have the skills, as things stand at the moment, to keep up with Stephen. However, I am always interested in thinking about and discussing how our current education systems could be improved, and what we might need to do to change them. I am also particularly interested in the underlying concepts, systems and ethics, i.e. the philosophical perspective through which we view education. It seems to me essential that this should underpin any discussion around ‘reinventing education’.

I regard myself to be adequately proficient with technology, but I don’t have the skills, as things stand at the moment, to keep up with Stephen. However, I am always interested in thinking about and discussing how our current education systems could be improved, and what we might need to do to change them. I am also particularly interested in the underlying concepts, systems and ethics, i.e. the philosophical perspective through which we view education. It seems to me essential that this should underpin any discussion around ‘reinventing education’.

Other ‘out of the box’ thinkers

Recently I find myself drawn to the thoughts of three well-known thinkers – two current and one from times past; Iain McGilchrist, Sir Ken Robinson, and Étienne de La Boétie (best friend of Michel de Montaigne).

Iain McGilchrist (in a nutshell) believes that our view of the world is dominated by the left hemisphere of the brain and that to save our civilisation from potential collapse we need more balance between the left and right hemisphere’s views of the world. I know this sounds melodramatic, but you would need to read his book The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, where he makes a very good case, backed up by loads of evidence, to find support for this claim. Later on this year, on a course offered by Field & Field here in the UK, I will be running a discussion group/workshop where I hope participants will share ideas about the possible implications of Iain’s work for rethinking education.

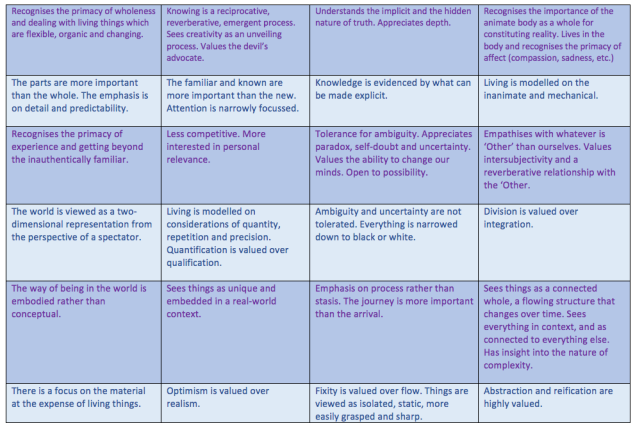

For those who are not familiar with the book, here is a Table* (click on it to enlarge) which briefly summarises some of the differences in the ways in which, according to McGilchrist, the left hemisphere and the right hemisphere view the world. The right hemisphere’s view of the world is presented in purple font; the left hemisphere’s view of the world in blue font. These statements have been culled from many hours of reading McGilchrist’s books and watching video presentations and interviews.

*I am aware that this Table is (necessarily) an over-simplistic, reductive representation of McGilchrist’s ideas. It cannot possibly reflect the depth of thinking presented in The Master and His Emissary. The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World. It is simply an introduction to some of McGilchrist’s ideas, which might provoke a fresh perspective on whether and how we need to ‘reinvent’ education.

In relation to McGilchrist’s work, my current questions are: Do we recognise our current education system in any of this? Do we need to change our thinking about education to achieve more balance between the left and right hemisphere perspectives?

Linked to McGilchrist’s ideas (and I will qualify this below, because it would be easy to get the wrong end of the stick), another ‘out of the box thinker, for me, is Sir Ken Robinson. Like many people, I first became aware of Sir Ken Robinson in 2006, when he recorded a TED Talk which has become the most viewed of all time ( 56,007,105 views at this time). The title of this talk was ‘Do schools kill creativity?’ and the thrust of the talk was that in our education system, we educate children out of creativity.

More recently in December of last year the question of whether schools kill creativity was revisited when Sir Ken Robinson was interviewed by Chris Anderson under the title ‘Sir Ken Robinson (still) wants an education revolution’. In this podcast the same question is being discussed more than ten years later and it seems that little progress has been made in ‘reinventing education’, at least in terms of creativity.

Just as McGilchrist is at pains to stress that both hemispheres of the brain do everything, but they do them differently, for example, they are both involved in creativity but differently, so Sir Ken Robinson says that we should not conflate creativity with the arts. The arts are not only important because of creativity; through the arts we can express deep issues of cultural value, the fabric of our relationship with other people, and connections with the world around us. Creativity is a function of intelligence not specific to a particular field and the arts can make a major contribution to this, but the arts are being pushed down in favour of subjects that are dominated by utility and their usefulness for getting a job. We are now locked into a factory-like efficiency model of education, dominated by testing and normative, competitive assessment.

In 2006 Robinson told us that education was a big political issue being driven by economics. He said that most governments had adopted education systems which promote:

- Conformity (but people are not uniform; diversity is the hallmark of human existence)

- Compliance (such that standardised testing is a multibillion-dollar business)

- Competition (pitting teachers, schools and children against each other to rack up credit for limited resources)

I am recently retired, so a bit out of the loop, but from my perspective not a lot has changed between 2006 and 2019, in the sense that education has not been ‘reinvented’ – notably there hasn’t been, at government and policy-making level, a change in philosophy. McGilchrist believes that our current approach, where left hemisphere thinking dominates, has significant negative implications for education; see The Divided Brain: Implications for Education, a post that I wrote in 2014 after hearing McGilchrist speak for the first time. Robinson believes that although some schools are pushing back against the dominant culture there is a lot more room for innovation in schools than people believe, that we can break institutional habits, and we can make innovations within the system.

But can we? What would this take? Would students and teachers be willing to risk ‘bucking the system’ to embrace an alternative, non-utilitarian philosophy of education?

I am currently reading Sarah Bakewell’s wonderful book about Michel de Montaigne – How to Live. A Life of Montaigne in one question and twenty attempts at an answer. In this she discusses the close relationship/friendship between Montaigne and Étienne de La Boétie and, in relation to this, refers to Boétie’s treatise ‘On Voluntary Servitude’. On p.94 she writes:

‘The subject of ‘Voluntary Servitude’ is the ease with which, throughout history, tyrants have dominated the masses, even though their power would evaporate instantly if those masses withdrew their support. There is no need for a revolution: the people need only stop co-operating ….’

Reading this immediately reminded me of the introduction in 2002 of the Key Stage 2 SATs (compulsory national Standard Assessment Tests) here in the UK – the testing of 11- year olds and the start of league tables pitting school against school. Key Stage 1 SATs (tests for 7-year olds) were introduced before Key Stage 2 SATs, so these teachers of 7-year old children had already been through the process. Therefore, by the time the Key Stage 2 SATs were introduced, schools and teachers had a very good idea of their likely impact, and Key Stage 2 teachers complained bitterly. I remember thinking at the time, if all the Key Stage 2 teachers in the country downed tools and refused to deliver the SATs, then there would have been nothing the government could do, but as Sarah Bakewell points out this type of collaborative, non-violent resistance rarely happens.

The power to change

Perhaps reinventing education will have to happen from the ground up, in individual classrooms/courses and institution by institution, rather than nationally. But how will this happen when the teachers and education leaders that we now have in place are themselves a product of an education system which has not: valued creativity as discussed by Sir Ken Robinson; a right hemisphere perspective on the world, as explained by Iain McGilchrist; or a rethinking of concepts, systems and ethics needed to take a new philosophical approach to education as envisaged by Stephen Downes?

This was the type of question that I had hoped would be discussed in the ‘reinventing education’ webinar that I attended earlier this week. It goes beyond tinkering – it’s more of a paradigm shift, or as McGilchrist says, it requires ‘a change of heart’. This is how McGilchrist sums it up:

… we focus on practical issues and expect practical solutions, but I think nothing less than a change of the way we conceive what a human being is, what the planet earth is, and how we relate to that planet, is going to help us. It’s no good putting in place a few actions that might be a fix for the time being. We need to have a completely radically different view of what we’re doing here.

Again, I want to make the case that ‘Edusemiotics’, the combination of the science of semiotics or the study of ‘sign action’ and educational philosophy, can be quite a powerful turn for the pragmatic development of teaching approaches and techniques that encourage creativity and the full recognition of the role of novelty in the pedagogical process.

It hinges on the whole concept of process-relational thought and metaphysics and the ‘reality of time’ which makes potentiality a reality.

Here are some relevant references to consider:

file:///C:/Users/garyg/Downloads/912-2626-1-PB.pdf A great paper by jazz musician and music teacher, Cary Campbell, who explores the idea of teaching an appreciation of the creative and the novel.

file:///C:/Users/garyg/OneDrive/Documents/Edusemiotics%20papers/Olteanu2016_Article_PredicatingFromAnEarlyAgeEduse.pdf

Great paper by Olteanu, Kambouri and Stables on the importance of personal connection and empathy in the teaching process (see also studies on Levinasian philosophy in education–topic for a separate discussion!) and how a semiotic orientation helps with the full recognition of pedagogy as a fundamentally relational enterprise in which teacher and learner are actually learning from each other, an acknowledgment and recognises the fundamental importance of ‘enhancing the possibilities of learning by acknowledging the learner’s preconceptions.’ Definitely worth careful examination, IMHO.

file:///C:/Users/garyg/OneDrive/Documents/Edusemiotics%20papers/pedagogy-and-edusemiotics%20Semetsky%20and%20Stables.pdf

A sampling of a book edited by Inna Semetsky and Andrew Stables called ‘Pedagogy and Edusemiotics which includes the TOC, Preamble, and first two chapters of the book. Definitely worth checking out.

and, finally, …but certainly not least,…

Click to access f2f41a15ad9528e5d689e766f84964dbaf47.pdf

A paper from the Journal of Philosophy of Education by Inna Semetsky called ‘Taking the Edusemiotic Turn. A Body~Mind Approach to Education.’ What can I tell you? This is a new vision of what education can become when it is taken beyond Cartesian mind-body dualism and into the realm of Peircean pragmaticism. What Semetsky proposes is a nondualistic approach to ‘integrative learning’ that, I would argue, is a fundamental necessity if we are ever going to hope to face and overcome the fundamentally existential global problems and proliferation of intellectual ‘dead ends’ that modernity has now thrust upon us as the Modern ‘Age of (disembodied) Ideas’ draws to a close.

While I think that it is important that we now have digital technology providing pedagogical opportunities that were never before envisioned, the opportunity to conference and communicate digitally across time and space like was never before possible, we must also carefully look at the philosophical and ethical issues from which we can no longer run away and just pretend that we can operate in a ‘business as usual’ mode. That is no longer going to be acceptable. Not if we hope that there will be a natural ecosystem on the planet that will continue to support human life fifty years from now.

All the signs are there. We are coming down to the wire rapidly.

And I would make the case that before things can move forward they must look backward.

Going back to understand the origins of pedagogies in earlier times would help us retrieve what works, or what is right, about education. I am continually astonished at the drive to create “new” approaches without examining the old, the tendency to instead simply declare the current system as “not working” and plunge headlong into new models.

Utilitarianism, semiotics, metaphysics, empathy – these aren’t new, nor are they new in their applications to education. If we are having some of the same conversations they had in the 17th century, wouldn’t it be best to study and acknowledge the work that’s already been done? The difficulty is in inherent short-sightedness and a delight in shiny objects, the belief that the approach must be “new” (likely to satify the givers of educational grants and such – I wonder if one could get a grant to promote the methods of Abelard in secondary schools?).

Looking at the wonderful McGilchrist-based chart above, it occurs to me that each item on it could engage a scholar in a lifetime of research, understanding the key arguments that have occurred repeatedly over the ages. One could do a historical study to discover what the similarities might be between our own time, and those earlier times where such ideas developed, and see how that might guide our thinking. The ideas of Montaigne, as you show here, are likely to be as important (dare I say more important?) than those of more recent vintage.

We also might consider that the aspects of the current system that are most criticized today may have a solid foundation in a number of these areas, and not reject them without subjecting them to critical analysis. I rarely see that. Mostly I see assumptions – the current system is poorly serving society and individuals, there isn’t enough x in education, there is too much y. The needs of the country, of the individual, of the world, are usually narrowly conceived by people and institutions very much situated in their own time.

Is anyone doing the historical work that needs to be done?

Thanks Gary for the information about Edusemiotics.

And thanks Lisa for your perspective that we could benefit from learning more from history, before plunging headlong into new models.

It would be hard to disagree with you, Lisa. Obviously we can learn a lot from history and even a limited knowledge of people like Montaigne and other Rennaissance and Enlightenment philosophers shows us that the issues that education struggles with today are not new.

A ‘historical study to discover what the similarities might be between our own time, and those earlier times where such ideas developed, and see how that might guide our thinking’, sounds like a fascinating project and probably one that would also take 20 years, as McGilchrist’s book did to write.

But what this raises for me is the question of how we use lessons from history to inform our present and future, given that we can’t go backwards, e.g. we cannot now have a world without digital technologies, or put another way, we cannot unlearn what we have learned. (You might disagree with this). So what are the limitations on what we can learn from history?

Oh yes, there are many limitations but I do think the limitations have been overemphasized.

Digital technologies are a perfect example. They seem so novel, and thus the solutions seem to require unique solutions. But each change in information technology have caused dislocations and impacts on education (and everything else). Printing would be the most obvious examples, the fear about which was pretty much the same as now: fake news, the implications of more open access to information, etc. How did educators and students handle the transition to print media? radio? television? To me, the conversations can start there.

Ironically, the work of historians on these subjects is buried in academic journals, but some of the specific work is being published by journalists. Tom Standage is a great example. In the tradition of Marshall McLuhan, his work on the history of technology is present-minded yet historically based.

So it’s not really a matter of going backward – doing history never is. It’s a matter of seeking back to find the threads that pertain, the ideas that need to be revived and discussed, the elements that may have been discarded but are now useful, technologically, ethically, and practically.

Thanks Lisa.

Thanks for sharing this valuable content, genuinely loved this