Module 7 of the National Gallery’s Introduction to Art History online course bring us up to the present day. The 20th century has seen a dramatic change in the visual arts, from representational works on canvas to conceptual art, so much so that the question ‘But is it art?’ has become a trope to describe the puzzlement felt by many towards ‘modern art’. An explosion of media has resulted in conceptual art, installations, interventions, performance and video art. In commenting on this period, Virginia Woolf wrote: ‘On or about December 1910, the human character changed.’

This module is being led by Lucrezia Walker, who got us off to a cracking, fast-paced start in Week 1, focussing on the theme of modernity.

Week 1. The shock of the new

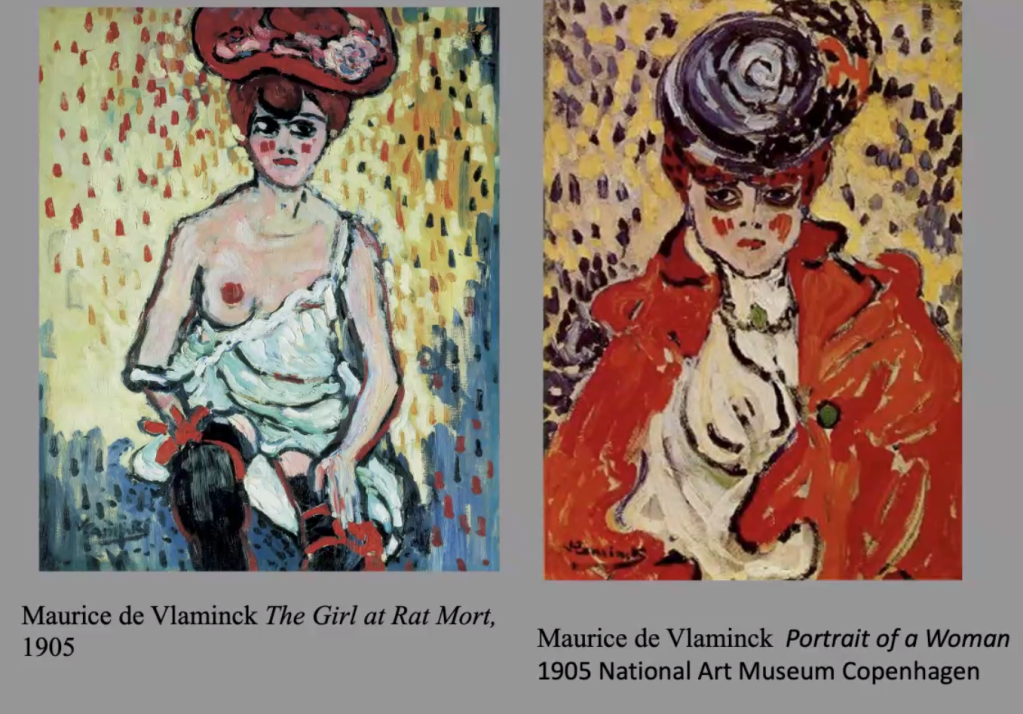

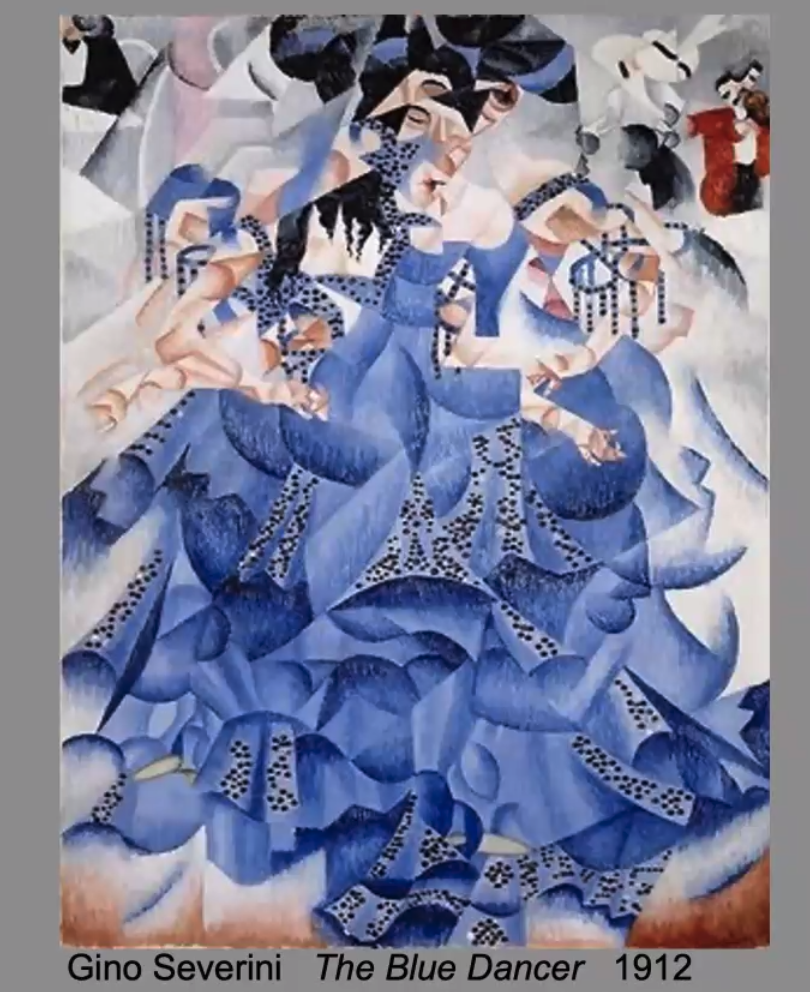

In this first two hour session we were introduced to the isms of the early 20th century: Fauvism, Cubism, Orphism, Vorticism, Expressionism, Futurism, Constructivism and Suprematism, and some of the iconic images of this period produced by Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Kazimir Malevich and Natalia Goncharova. Also mentioned were George Braque, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, Sonia Delaunay, Robert Delaunay, Gino Severini, Umberto Boccioni and Liubov Popova.

(Interestingly, and as an aside, I am currently reading John Dewey’s book, Experience and Education. In his Preface he writes:

‘… any movement that thinks and acts in terms of an ‘ism becomes so involved in reaction against other ‘isms that it is unwittingly controlled by them.’

I think this statement by Dewey, although written in the context of education, is pertinent to a discussion of modern and contemporary art. )

I really enjoyed this week. Lucrezia Walker managed to convey the dynamic, bursting energy of the era, as she whisked us through many, many slides, vibrant with colour and movement. She started with Fauvism and the use of bright, prismatic, strong, naturalistic, unmixed colour applied directly from the tube, particularly in the work of Matisse, Derain and Vlaminck.

This experimentation with colour and style was heavily criticised, but fortunately for Matisse his work was bought by Gertrude Stein, an important patron, as was the work of Picasso, who took seriously Cezanne’s comment that ‘Everything in nature is formed upon the sphere, the cone and the cylinder. One must learn to paint these simple figures and then one can do all that he may wish’. This influence is very recognisable in Cubism. Picasso was described as an artist who could paint like a genius but was looking for more authentic ways of painting than the traditional.

In the second half of the session Lucrezia Walker spent some time on the Futurists, who were influenced by Henri-Louis Bergson’s work on time, past, present and future, and their extraordinary manifesto. It’s not surprising that they had to draw back from their fighting talk (see point 9 in the manifesto), when one of their influential members, Boccioni, died in World War 1.

The Futurists, were fascinated by movement and shapes in flux, produced some wonderful work, too much to cover here, but Gino Severini was a leading artist in this movement.

Futurism ultimately led to increasing abstraction and artists such as Malevich (Suprematism) and the influential work of the constructivist movement in Russia. See, for example, the work of Liubov Popova.

Week 2. The road to abstraction

This was another fascinating week in which, through looking at the work of Wassily Kandinsky (in the first hour of the two-hour lecture), and Piet Mondrian (in the second), we saw a move away from the figurative and recognisable, to increasing abstraction, with a focus on colour and shape.

Kandinsky was the son of prosperous parents. He trained at art school in Odessa, but also qualified in law and economics at the University of Moscow. He began painting at the age of 30.

Lucrezia Walker took us through Kandinsky’s four steps to abstraction. (Much of the text below is taken from her slides).

- In 1889 Kandinsky was part of an ethnographic research group which travelled to the Vologda region north of Moscow. In Looks on the Past, he relates that the houses and churches were decorated with such shimmering colours that upon entering them, he felt that he was moving into a painting. His painting became inspired by the Bavarian countryside and folk imagery from Russian fairy tales.

- In 1896 Kandinsky saw a Monet exhibition and wrote: “That it was a haystack the catalogue informed me. I could not recognise it. This non-recognition was painful to me. I considered that the painter had no right to paint indistinctly. I dully felt that the object of the painting was missing. And I noticed with surprise and confusion that the picture not only gripped me but impressed itself ineradicably on my memory. Painting took on a fairy-tale power and splendour.” At this point, for Kandinsky, the subject of a painting decreased in importance.

- Kandinsky’s work was influenced by Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin, when he became interested in how music makes us feel. He likened painting to composing music, writing, “Colour is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the piano with many strings. The artist is the hand which plays, touching one key or another, to cause vibrations in the soul.” Also, at this time he was spiritually influenced by Madame Blavatsky’s work on theosophical theory, the esoteric and mystical.

- Kandinsky’s work became increasingly abstract under these influences, and he began to think that shapes have certain colours, for example, a circle is blue, a triangle is yellow, and a square is red. All these influences came together in his work Composition No. 4

From this time on, Kandinsky’s work became increasingly abstract. By 1923 abstraction completely eclipses the figurative in Kandinsky’s work.

There was a lot more said about Kandinsky in this session that I do not have space to cover here, but Wikipedia provides a good overview of his life and work.

Kandinsky is thought to be the first abstract painter, but Lucrezia Walker showed us the work of Hilma af Klint, Georgiana Houghton and Emma Kunz, all of whom were producing abstract work earlier than Kandinsky. However, perhaps because they were inspired by theosophy, interested in healing and mysticism, experimenting with symbolic investigation, and claimed to be guided by the spirits, they were not taken seriously, and their work was not included in later exhibitions alongside Kandinsky and Mondrian.

In the second half of this session, we had an equally in depth look at the work of Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), who took abstraction even further. What I didn’t know about Mondrian was that originally his name was spelt Mondriaan. He changed it in 1912 after seeing cubist art in Paris. Mondrian started work as a post-impressionist, but by 1908 his work was becoming more abstract, and by 1914 it was completely abstract. Like Kandinsky he was very interested in theosophy and tried to take what he saw from the outside world and distil it down for spiritual resonance. He was looking for harmony and rhythm, and trying to get as close as possible to the truth. Lucrezia Walker’s text on this slide below explains Mondrian’s approach to the use of primary contradictory colours.

We were shown many more slides of Mondrian’s work, which has been very influential on the work of other artists, such as Roy Lichtenstein, fashion design and commercial design, e.g., the Rubik cube.

Week 3. Dada and Surrealism

This was another intense week which covered far more than I could possibly recount here. The session was in two parts, with input on the radical anti-art movement, Dada, covered in the first half and Surrealism covered in the second half.

Dada was quite a short lived movement (1915 – mid 1920s) born out of negative reaction to the horrors of WW1. It was begun by a group of artists and poets associated with the Cabaret Voltaire, a nightclub started by Hugo Ball in Zurich. The Cabaret Voltaire was only open for a few months, but the group of poets, performers and artists who presented their work there, created an entirely new sensibility which was to have a century of ramifications.

‘Dada rejected reason and logic, prizing nonsense, irrationality and intuition. It was an anti-art art, and a state of mind and being. The origin of the name Dada is unclear; some believe that it is a nonsensical word. Others maintain that it originates from the Romanian artists Tristan Tzara’s and Marcel Janco’s frequent use of the words “da, da,” meaning “yes, yes” in the Romanian language. Another theory says that the name “Dada” came during a meeting of the group when a paper knife stuck into a French–German dictionary happened to point to ‘dada’, a French word for ‘hobbyhorse’.’ (text from Lucrezia Walker’s handout)

What is Dada?

This video covers much of what we were introduced to in the first half of this session, but Marcel Janco’s and Kurt Schwitters’ work was used to illustrate the Dadaists’ use of low art materials, such as cardboard, and Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp were both referenced in relation to work that used ‘found objects’ and work that raised the questions ‘What counts as art? What is art? Is anything in an art gallery art? New to me in this session, was Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau (Merz building). This extraordinary work no longer exists as it was destroyed in the war.

Ultimately Dada morphed into Surrealism. This movement was founded in Paris in 1924 by a group of poets, painters, and filmmakers. Instrumental in this was the writer and poet André Breton. Breton studied medicine and psychiatry, and was very interested in the disturbed mind and a proponent of automatic writing, which led to him authoring the First Surrealist Manifesto in 1924.

The Surrealists were inspired by the power of the unconscious mind – a concept Sigmund Freud had made famous. They saw the unconscious (revealed most clearly in dreams) as the source of all imagination and believed that art should try to express its contents. The word surreal has entered the lexicon to describe situations that strike us as dreamlike. Key elements in Surrealist practice are the random and the unexpected, chance and coincidence, sex and desire.

What is surrealism? This video attempts to answer this question.

Salvador Dalí was the most prominent and probably best known Surrealist, and we were shown many slides of his work in the second half of this week’s session.

We were also shown work by Giorgio de Chirico, René Magritte (the second most famous Surrealist), Max Ernst, Joan Miro, and Dora Maar, amongst others.

‘Surrealist painting generally fell into two distinct categories. Artists including Salvador Dalí, René Magritte and Yves Tanguy, made hyper-real paintings with dream-like subjects depicted in minute precision, adding to their otherworldly quality. Other painters such as André Masson explored automatism, tapping into their unconscious mind to create expressive images. Breton defined automatism as, ‘pure psychic automatism … the dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason and outside all moral or aesthetic concerns’. Other artists such as Joan Miro moved between the two styles, and frequently used both techniques within the same work of art.’(text from Lucrezia Walker’s handout)

For the Surrealists beauty was to be ‘convulsive’ and came about by chance. Objects which bore no reference to each other derived new beauty or significance through random juxtaposition.

Week 4. Abstract Expressionism to Pop

The first half of this week was presented by Guest speaker Chloe Julius, University College, London. I found this session difficult to follow as she showed 93 slides in less than an hour, and the work of so many different artists that it’s difficult to know where to start in trying to summarise this. Among the artists she mentioned were: Mel Bochner, Frank Bowling, Yayoi Kusama, Anne Truitt, Andy Warhol, Lee Krasner, Willem De Kooning, Helen Frankenthaler and Barnett Newman. Maybe I found this session difficult to follow because, for the most part, this art doesn’t resonate with me. Or perhaps the problem with this session was that there was just too much to take in and I didn’t get a sense of what the key points were. The Tate Gallery explains Abstract Expressionism on their website and The Royal Academy has published a beginner’s guide, both of which I find helpful. The Tate Gallery also explains Pop Art on their website. I have chosen one of the slides of Barnett Newman’s work to share here, since Newman was considered a leading figure in Abstract Expressionism.

I found the second half of this week much more interesting. Lucrezia Walker is a very good storyteller, and she also appreciates that less can be more. There were only 38 slides in this session, which focussed mainly on the action painter Jackson Pollock, and the colour field painter Mark Rothko.

‘Pollock famously placed his canvas on the ground and danced around it, pouring paint from the can or trailing it from the brush or stick. In this way, the action painters directly placed their inner impulses onto the canvas.’ (Text from Lucrezia Walker’s handout).

In this photo we see Pollock working, with his wife Lee Krasner in the background. Krasner was also an artist but only became successful after Pollock’s death. At this time there were other artist couples, where the wives tended to be marginalised, e.g. Willem de Kooning’s wife, Elaine de Kooning, and Robert Motherwell’s wife, Helen Frankenthaler.

Mark Rothko was a colour field painter. He painted large canvases of more or less a single flat colour, intended to produce a contemplative or meditational response in the viewer, a transcendental moment, a religious experience. Rothko wanted his paintings to be about tragedy, ecstasy and doom, and to be the visual equivalent of music. When exhibited, he insisted that his canvases were not glazed or framed and were placed low down on the wall near the floor. Both Pollock and Rothko epitomised the artist as tortured genius. Rothko committed suicide, and Pollock died in a car crash as a result of driving under the influence of alcohol.

This session ended with a brief reference to Pop artist Andy Warhol, who evidently hated Abstract Expressionism, thinking that his work was more democratic. Warhol worked in his studio, which he called The Factory, with a team of people. Rothko worked on his own. Andy Warhol’s popular art was about popular things such as Campbell’s Soup Cans. Roy Lichtenstein was also a Pop artist, who took non high art images and made them big, i.e., he made big art out of things that are not important.

Week 5. YBAs (young British artists) and who writes the canon

At the start of this week Lucrezia Walker had to point out, following questions about this, that she is not able to cover every significant artist of the period in her lectures. In the first half of this session, she showed us the work of some of the better known young British artists and discussed some artists who never made it into the canon (the agreed list of artworks that is valued and considered worthy of study).

The YBAs (noted for ‘shock tactics’) caused a sensation when a collection of their work, owned by Charles Saatchi, was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1997. The exhibition was aptly called Sensation and generated controversy, particularly in relation to Marcus Harvey’s’ huge depiction of Myra Hindley, made of hundreds of copies of a child’s handprint (ink and eggs were thrown at this picture), and in relation to Chris Ofili’s controversial painting, The Holy Virgin Mary. The painting depicted a Black Madonna surrounded by images from blaxploitation movies and close-ups of female genitalia cut from pornographic magazines, and elephant dung.

Many of the works in the exhibition were considered offensive, or even ‘rubbish’. See Late Review – Sensation Exhibition – for an entertaining short video on this. Exhibiting artists included Damien Hirst (Lucrezia Walker showed us many examples of his work), Tracey Emin (her unmade bed and tent naming all the people she’d ever slept with), Marc Quinn (who used his own blood to make self-portraits), Rachel Whiteread (who fills empty spaces), Cornelia Parker, who blew up a shed (blown up by the British Army) then hung the pieces to look like an explosion, and Mark Wallinger (best known for his sculpture for the empty fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square, Ecce Homo (1999). See this video, Threshold to the Kingdom, for another example of his work.

Lucrezia Walker described Damien Hirst as a genius, who has gone from strength to strength. He not only knows how to create the impossible and extraordinary, and the value of a gimmick (dead animals in formaldehyde), but having worked in an art gallery, he understands how to get people like Saatchi on board. Lucrezia pointed out that some other artists today have also realised that they can exploit a gimmick, e.g., Grayson Perry and his alter-ego Clare.

But there are some artists who have not been collected despite the quality of their work. Although Jenny Saville’s work was included in the Sensation exhibition, her work has not been as sought after as Hirst’s or Emin’s. For example, the Tate has work by Tracey Emin, Sarah Lucas, Angus Fairhurst, Mat Collishaw, Cornelia Parker, and Tacita Dean, but not by Jenny Saville.

This has also happened to other artists. Michael Andrews’ work was valued alongside Frances Bacon’s and Lucien Freud’s until he moved out of London to Norfolk for a quieter life with his family, when he lost his place at the centre of things. And Jack Vettriano, a self-taught artist, who began painting at the age of 19, and who sells more in reproductions than anyone else in Britain, doesn’t have a gallery that represents him.

In the second half of this week’s session, artist Raksha Patel discussed aspects of her practice and how seeing the Sensation exhibition influenced her practice.

You can read about Raksha’s work at https://iniva.org/library/digital-archive/people/p/raksha-patel/ and see some of her works and hear her talk at https://consideringart.com/2021/08/09/considering-art-podcast-raksha-patel-painter-and-filmmaker/

Week 6. Where are we now: women, diversity and collectives

This final session of this module started with a look at how difficult it has been for female artists to be considered seriously. This attitude started to change in 1961 with the art of Nicky de St Phalle who created paintings by shooting at bags of paint on a canvas and allowing the dripping paint to create the image. This image of a woman yielding a fire-arm was in direct opposition to the usual image of women seen as nude models for art, as seen in Yves Klein’s Anthropometries series (Performance art), where he used nude female modes as ‘living brushes’.

This kind of male dominated art ultimately led to the Guerrilla Girls pushing for feminist art (and change), with their text-based, funny images, which incorporated clear messages of gender politics. Below is one of their best known images, but there are many more.

The Guerrilla Girls are also an example of an activist collective.

We then went on to look at the wonderful work of Frida Kahlo, who was well known by her death and portrays herself as psychologically raw in a mixture of realist and surrealist styles.

And we also saw, amongst others, the work of Paula Rego. I specifically mention her, because I will see her work at the Tate, when I visit London next month.

Diversity was discussed in this session by looking at the work of Zanele Muholi (a South African visual activist and photographer) and Yayoi Husama, whose work I was lucky enough to see at an exhibition in Denmark in 2017.

The session ended with a fascinating look at the work of street artists and a discussion of how this impacts on the art market. How do street artists make their money? In particular we looked at the work of Banksy. Lucrezia Walker suggested that Banksy makes his money because his work is well executed, often politically engaged and funny. What I found interesting was that Lucrezia told us that she knew the name of Banksy, but she didn’t divulge it. It seems important that we don’t know the true identity of Banksy, who for the general public, like me, remains anonymous, creating his graffiti art works beyond the public eye.

Jean-Michel Basquiat was also a promising graffiti artist, who unfortunately died young, at the age of 27. We had a brief look at his work.

As ever, there was far too much in this session and module to cover in one blog post, but let’s end with two challenging statements. Do you agree with them?

Every Man is an Artist – Joseph Beuys

Without the viewer there is nothing – Olafur Eliasson (i.e., the artist is nothing, the viewer is everything)