This is the first module of The National Gallery’s Stories of Art Online course. The course consists of seven modules, each lasting six weeks (and thus the course runs for a year from September to August), starting with the art of the 13th and 14th centuries, and ending with 20th and 21st century art.

I have already completed modules 2 to 7 (search under the category Art History, or the tag National Gallery on this blog for previous posts), but I missed this first module, not having been aware of it at the time, hence working on it now. It is quite a jump to go from 21st century art and, for example, the work of street artists such as Banksy, back to the 13th century and the work of Giotto.

Module 1 is being presented by Siân Walters, who is not a new face to me, since she helped out on many of the other modules by working in the background to answer participants’ questions.

Week 1: Overview

Week 1 of Module 1 started with an overview of the period. This was the introductory text provided by Siân Walters in the handout.

During the High Middle Ages, many cities in Italy began to assert their autonomy and new models of government evolved. Increased urbanisation led to a rise in art patronage: vast cathedrals were built to accommodate increasing populations and large numbers of works of art were commissioned for the decoration of churches, as well as for private devotion. In this session we will look at the context in which art patronage evolved with reference to the emergence of the mendicant orders, notably the Franciscans. We will also consider the predominant Byzantine style of the 1200s and early 1300s and the influence of non-Western culture on Marian iconography, such as the cult of the Black Madonna.

I am not going to write about this overview, but instead focus on what was most interesting for me in this week, which was the recognition that art history did not start with the Renaissance, but that the Renaissance was influenced by the art that preceded it. Particularly interesting for me was how influential was the work of Giotto, who changed the course of art history and has been called ‘The Father of Western painting’.

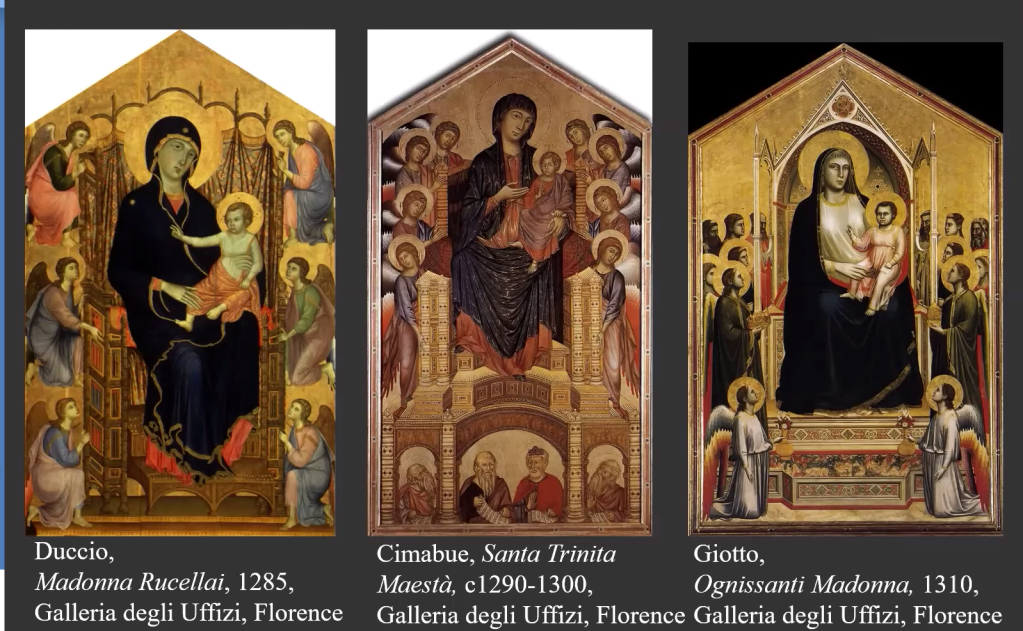

Giotto’s influence in this period cannot be overestimated. He was brought up under the influence of Byzantine art, but unlike the flat, iconic, stylized painting of that tradition, Giotto’s work was realistic and three dimensional. His incredibly expressive paintings were an absolute revelation in terms of his approach to narrative and execution. No-one had seen work that was so realistic and tangible in the early 1300s. Giotto was a wonderful storyteller and a great innovation was his emphasis on human emotion.

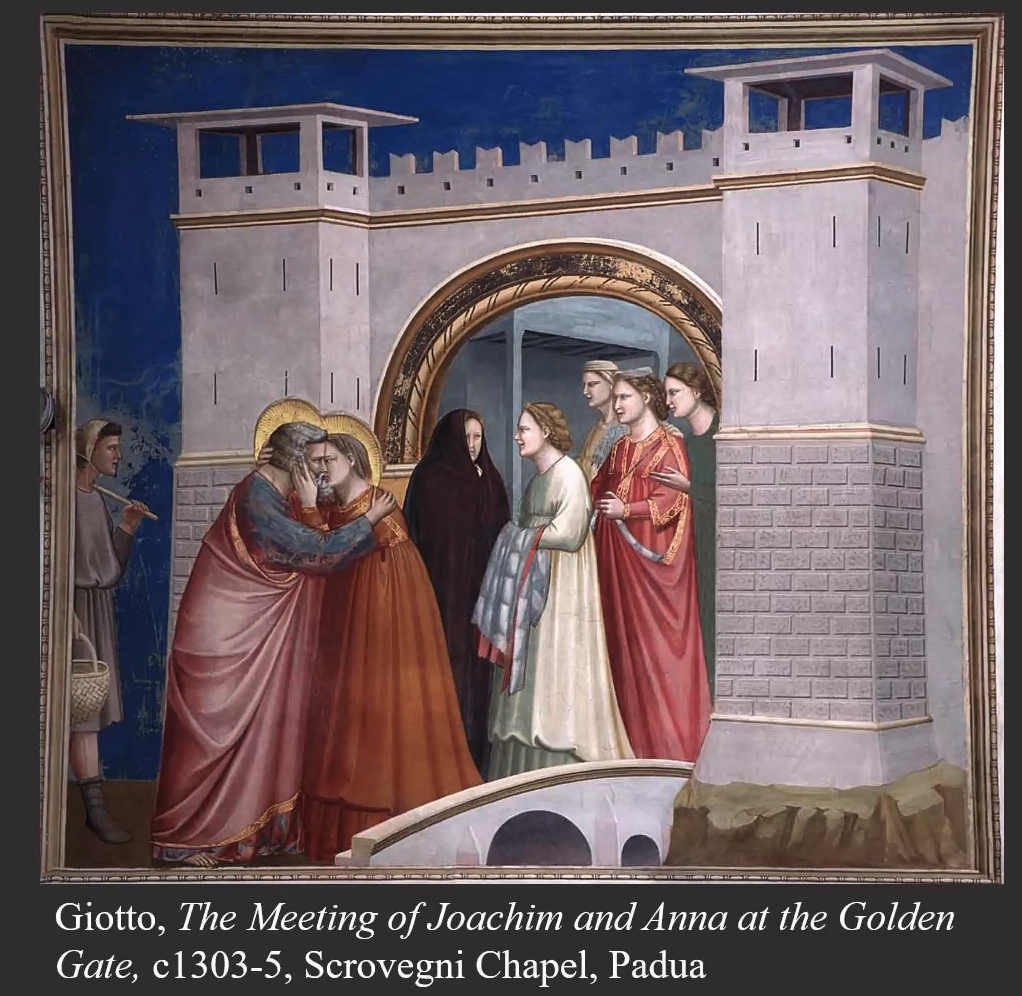

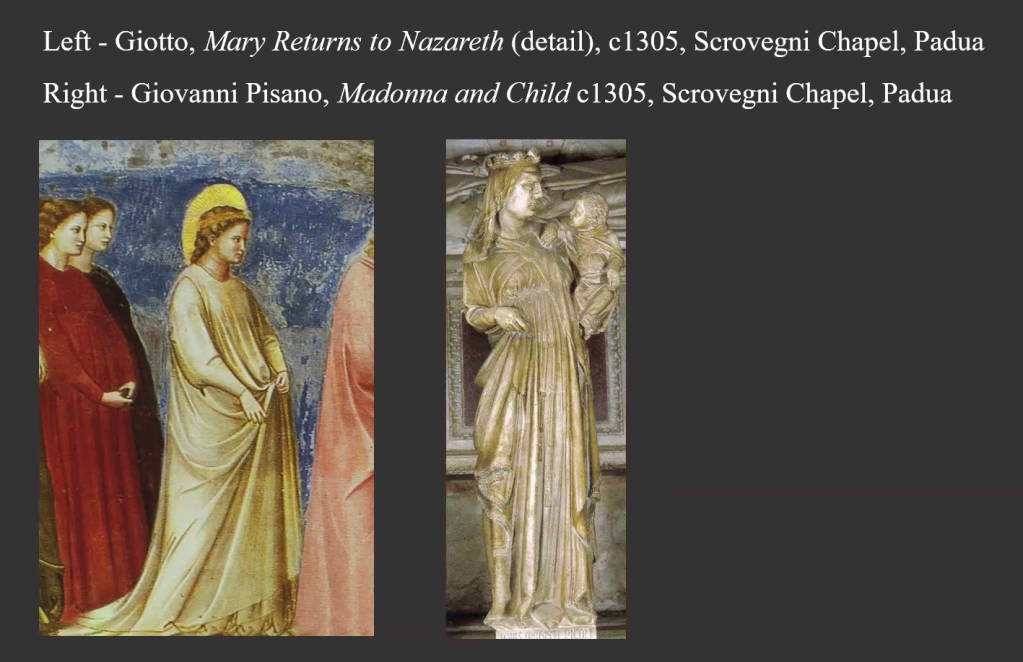

Giotto was the first artist since Roman times to employ perspective in the way he did, and he was the first artist to use a cropping device (see the cropped figure on the left in his painting of The Meeting of Joachim and Anna at the Golden Gate). Siân Walters also suggested that Giotto drew some inspiration from sculpture and the way folds in clothing was depicted in sculpture. This was a common way of working 100 years later in the 1400s, but not in the time of Giotto.

There was of course a lot, lot more in this first week of the course than I am covering here, and many, many more slides. We considered key forms of patronage in this period, looked at the historical, social, and political background in Italy at this time, considered how sacred and secular artworks functioned in different ways, and examined how painting developed stylistically from early works under Byzantine influence to later paintings by Giotto. I have focussed on Giotto, who was a revelation to the art world of the 13th century, but also a revelation to me in the 21st century.

Week 2: Artist in Focus: Duccio

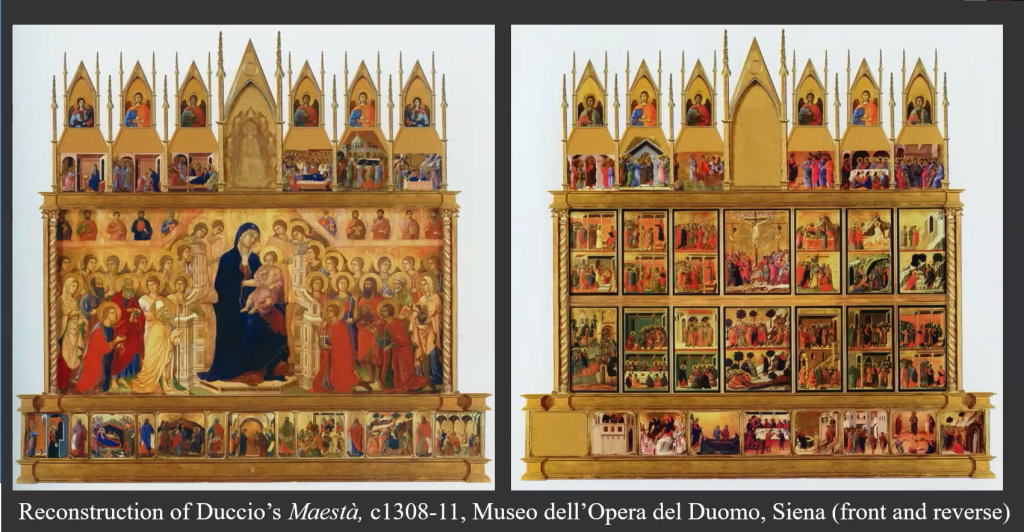

The 1300s was the Golden Age of Sienese painting. Its leading artist Duccio di Buoninsegna was one of the most innovative and influential figures in Western art, introducing a new naturalism and interest in space, structure and emotion which would bridge the gap between the Byzantine idiom and a new, modern style. In 1311, he completed the city’s most famous altarpiece, the Maestà, for Siena Cathedral and a number of its panels can now be found in the National Gallery. (Text from the course handout)

The Maestà is a very large work, 7ft x 13ft, which Duccio, according to the terms of his contract was expected to work on alone, although Siân Walters thought this must have been impossible. It was a huge undertaking, not only in terms of its size (it consists of 59 panels), but also because it was painted on the front (for the congregation) and the back (for the clergy).

Duccio was working at the same time as Giotto, but Giotto became more famous, perhaps because Giotto worked in Florence and Duccio in Siena, and also perhaps because Giorgio Vasari, a 16th century art historian best known for his ‘Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects’, mistakenly attributed some of Duccio’s work to his teacher Cimabue. There is not a lot of documentary evidence of Duccio’s life, but from surviving documents we know that he was a headstrong individual, who at times was in trouble with the law.

Despite not being as famous as Giotto, Duccio was famous in Siena and was paid 3000 gold coins for Maestà, which was an astronomical sum at the time.

Both Duccio and Giotto brought a more human approach to painting. Their style was more realistic than other painters of their time, as can be seen from the comparison of their work with that of Cimabue in the image above.

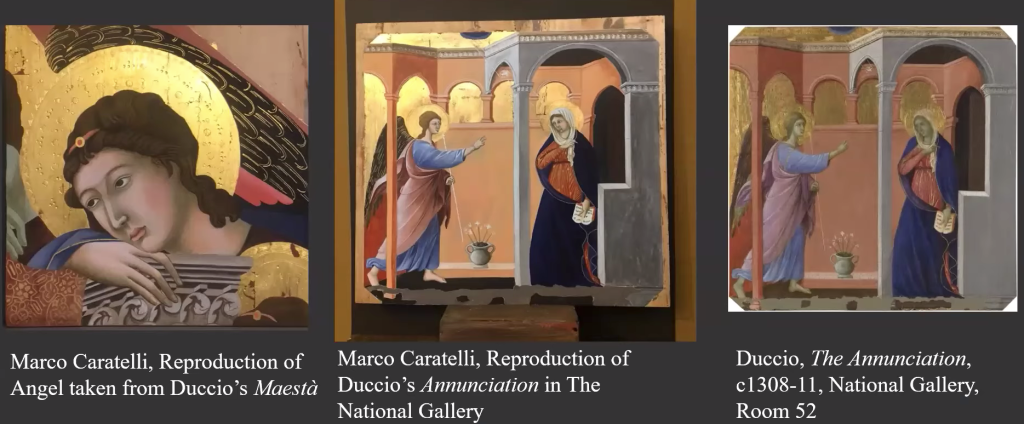

The work of Duccio and Giotto, as can be seen from the images posted, made extensive use of gold leaf. In the second half of this week’s session we were taken on a private, virtual visit to the art studio of Marco Caratelli in Siena, who showed us how he replicates the work of the great Sienese masters, such as Duccio, and the techniques he uses including the application of gold leaf.

Marco’s ‘bible’ is Cennino Cennini’s ‘The Craftsman’s Handbook’, published over 600 years ago, which describes how artists of the time applied gold leaf. The book can still be bought online. This short video gives you a flavour of what we saw https://youtu.be/PTbBCjCv3vg which was fascinating. Such patience is needed!

Week 3: Symbols

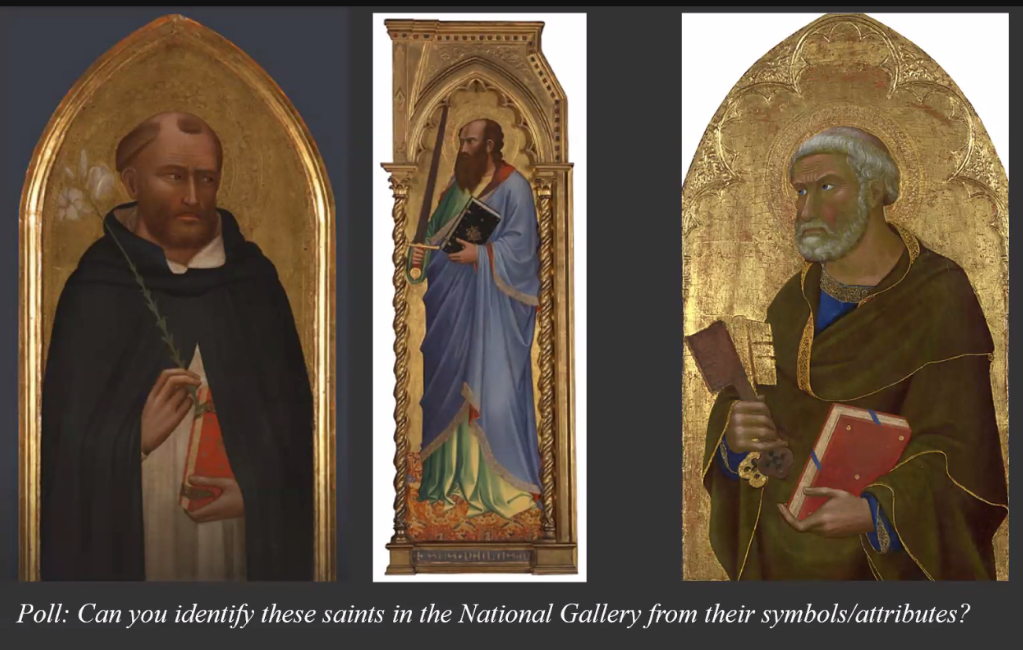

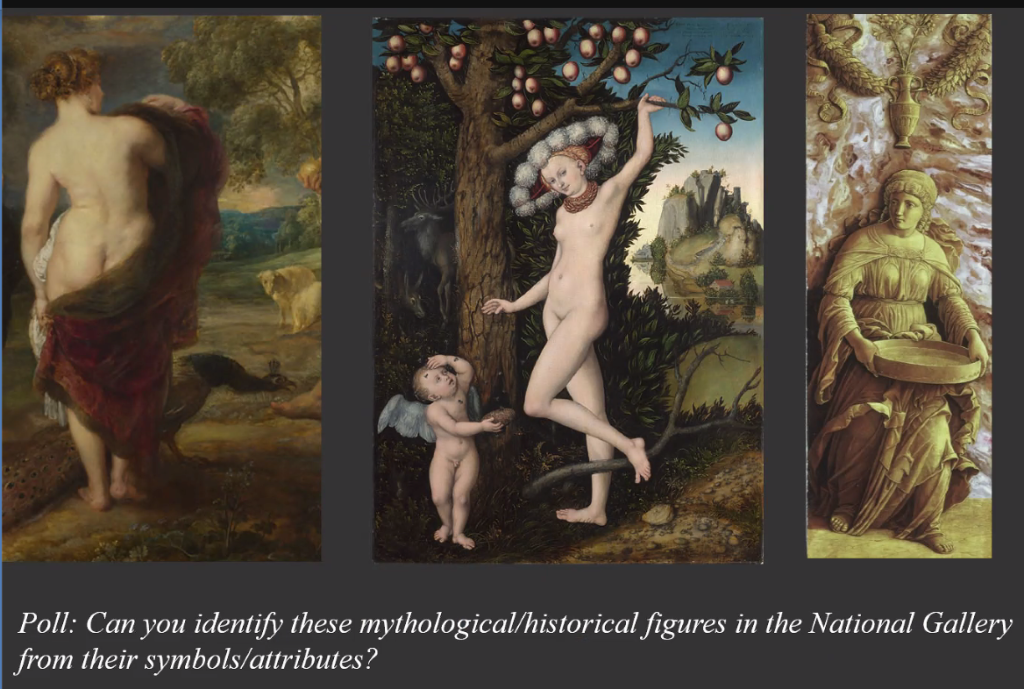

The key question this week was ‘How can we decipher a painting through its symbols?’ The focus was on iconography and the language of symbols in the 13th and 14th centuries. Iconography is essential to the study of the history of art and the language of symbols changes over time, but in the 13th and 14th centuries, when illiteracy rates were high, paintings were made to speak to the people and the use of symbolism meant that they could be more easily understood. For example, a dove in a painting represents the Holy Spirit, a lily represents purity and chastity, and the halo is a symbol of holiness. Colours were also used as symbols; gold represents divinity and purple represents royalty. Figures in paintings can often be identified by the colour of their clothing; the Virgin Mary is often painted in blue and read, St. Peter in blue and gold. Siân Walters devised a number of polls for this session. Here are screenshots of two of them.

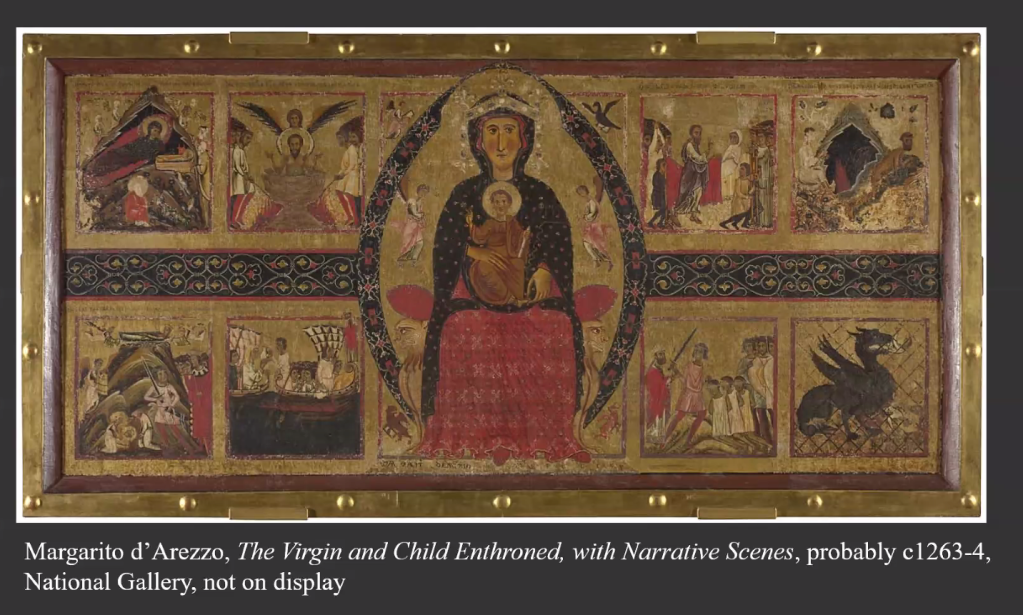

As well as being shown a number of slides of paintings which include symbols, quite a bit of time was spent looking closely at Margarito d’Arezzo’s painting, The Virgin and Child Enthroned, which is full of symbolism and narrative. Note the mandorla (the almond shape enclosing the Virgin Mary) which symbolises eternity. This is one of the very few signed paintings of the era. Margarito was a prolific and very important artist in the 13th century who drew on sculpture and byzantine painting for inspiration and was a wonderful storyteller. Painted around 1263, this is the oldest picture in the National Gallery’s collection.

In the second hour of Week 3, Peter Schade, Head of Framing at the National Gallery introduced us to the stylistic evolution and the development of the frames of the National Gallery’s paintings. He described how he sources, creates, and adapts examples which complement the paintings historically. Here is an example of a frame he is working on. Nardo di Cione, Three Saints – about 1363-65

And here is a short video which gives a taste of what Peter’s work involves: https://youtu.be/1sR2g9dN9dM

Week 4: Context

This week the question raised was ‘How do paintings function differently in museums from their original locations?’ ‘Most of the works commissioned during the Medieval and early Renaissance period were designed for worship and yet very few of them remain in their original location, calling into question how we can interpret and view these works in a museum context’ (text from Siân Walters’ handout). Many of the works of this period were designed to be seen in dark churches and lit by candlelight. They were also designed as altar pieces to be hung high up, so that the view of them could not be obscured. If the centre of the painting was going to be obscured by a large cross on the altar, then that section of the painting included very little detail and no content of importance.

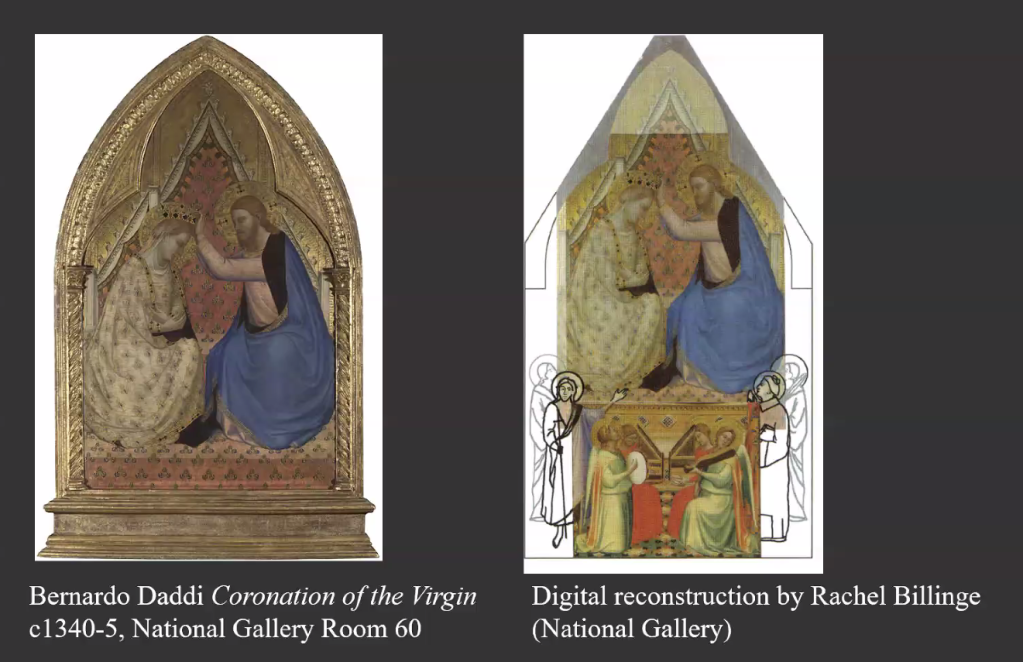

A lot of these paintings were very large, often with many panels. In the 1700s and 1800s, when the monasteries and convents were suppressed, many of these paintings were split up and the panels dispersed. There is evidence of this in Bernardo Daddi’s , The Coronation of the Virgin, c.1340-5. National Gallery. Room 60, where a digital reconstruction by Rachel Billinge, shows how the painting has lost some of its original content.

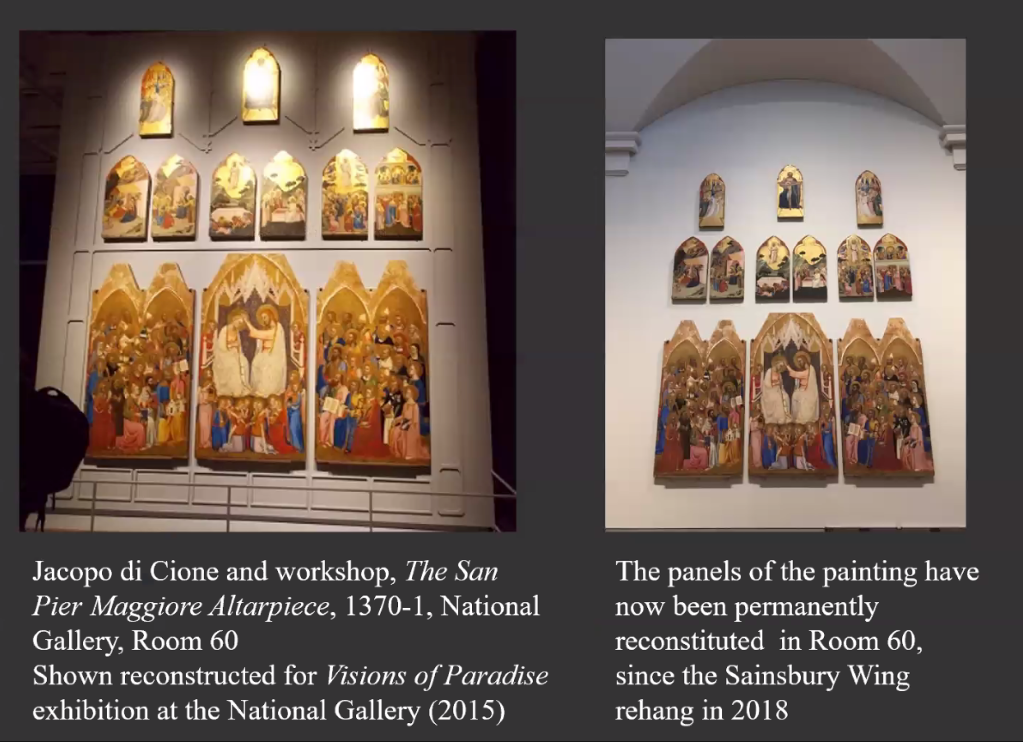

Some exhibitions try to bring the dispersed panels together again, as in the case of Jacopo di Cione’s The San Pier Maggiore Altarpiece and workshop,1370-1. National Gallery. Room 60

We also looked at Duccio’s, Maestà Predella Panels, c. 1307/8-11. National Gallery. Room 52, in relation to this week’s topic of context. This is what is written on the National Gallery’s website about this work:

There are different ideas as to the location of this high altar and why the altarpiece was double sided, but it is likely that the congregation had access to both sides. By 1506 the Maestà had been removed from the high altar and in the late eighteenth century it was sawn in half, causing damage to the Virgin’s face. Some fragments were sold and are now scattered across international collections; a few are now missing. The majority of it remains to be seen in the Museo dell’opera del Duomo in Siena.

Another work where knowledge of the original location helps in understanding its function is Andrea di Bonaiuto da Firenze’s, The Virgin and Child with Ten Saints, c.1365-70. National Gallery. Room 51

And I wasn’t aware before this session of Bonaiuto da Firenze’s amazing frescoes in the Spanish Chapel, 1365-7, Santa Maria Novella, Florence. I hope I will be able to see these in situ one day.

From all this it is clear that museums and galleries, such as the National Gallery, have their work cut out for them in trying to display their paintings as authentically as possibly. It is limited in what you can do in a gallery environment, but digital visualization techniques are beginning to help address some of the problems. See for example the Hidden Florence website for a flavour of how the locations, in which some of these paintings originally hung, can be recreated.

Week 5: Technique

The first half of Week 5 was led by Siân Walters, and the second half by Rachel Billinge, Research Associate in the National Gallery’s Conservation Department.

Siân Walters explored the ways in which art was created during the Medieval and early Renaissance period, focussing on two main techniques, egg tempera and fresco, as well as the development of oil painting in Northern Europe. She referred again to Cennino Cennini’s book, The Craftsman’s Handbook, as the source of practical advice, and guide to techniques used in this period.

Egg tempera was a technique used in most early Italian panel paintings. Colours were mixed with water and then bound (tempered) with a glutinous water-soluble bind medium, usually egg yolk. There are five stages to the egg tempera technique.

1. The wood panel is prepared by a joiner; the type of wood depends on what is available

2. The wood is smoothed with Gesso

3. The preparatory drawing is made on the surface of the panel

4. The preparatory drawing is covered with Bole (a kind of red clay used as a preparatory layer prior to the application of gold leaf in panel paintings)

5. Pigment bound with egg is applied to the areas of the drawing not to be gilded. Very fine brushes were used to do this, often made of squirrel fur. Lapis Lazuli was a very expensive pigment at the time, more expensive than gold, and a common pigment was terre-verte, applied under skin tones. Paintings from the 1300s, in which skin tones now appear green, would have had pink skin tones at the time. The pink has now faded to reveal the green underneath.

Both Jacopo di Cione and workshop’s The San Pier Maggiore Altarpiece and Duccio’s The Virgin and Child with Saints Dominic and Aurea, were made using the egg tempera technique.

The term fresco [Italian: affresco] means fresh because the paint is applied on a fresh and wet layer of plaster, with the pigments dissolving into the lime water. As both the paint and plaster dry, they integrate completely. The pigment is absorbed and becomes part of the wall, rather than simply adhering to the surface as with other painting techniques. With the true fresco or buon fresco technique, the artist must apply his colours onto the wet plaster as soon as it has been prepared and laid on to the wall. (Text from Siân Walters’ handout).

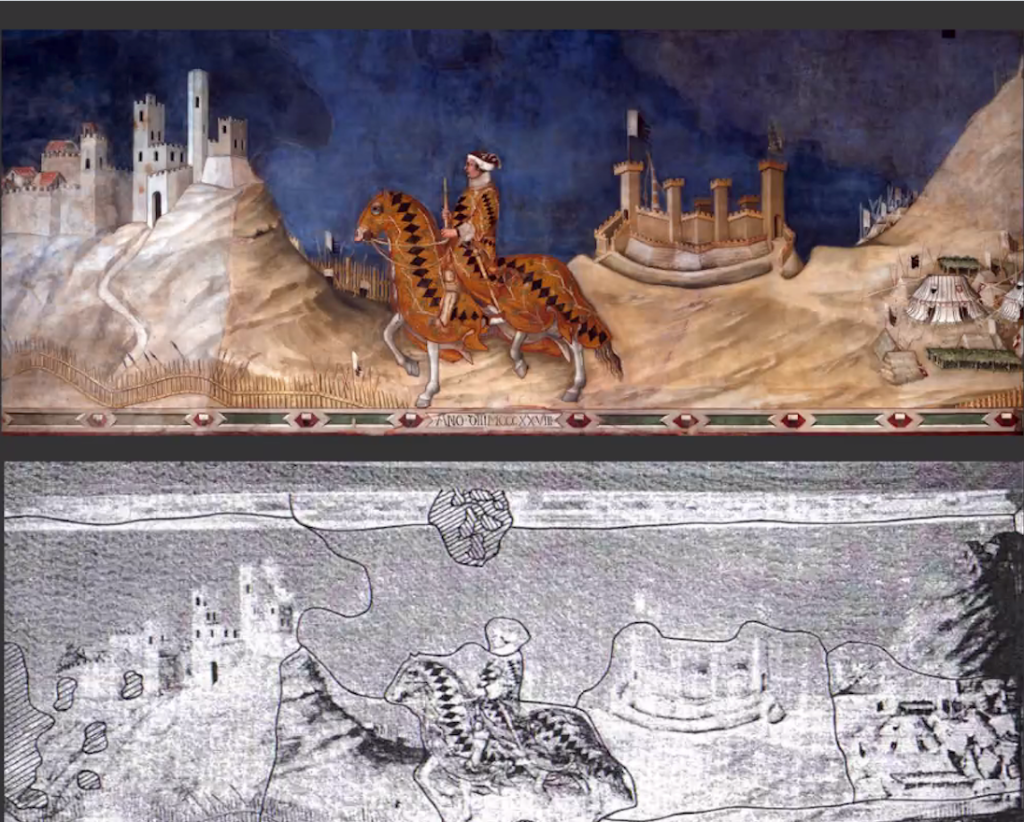

As for the egg tempera technique, we were taken through the steps of how to create a buon fresco, and there was also some discussion of fresco secco, how fresco artists used cartoons to transfer their drawings to the prepared plaster, and how sections of plaster were worked on within specific time durations before the plaster dried (usually a day, Giornata). This image below shows how if you look carefully at a fresco, you can see the different sections that were painted on different days after fresh plaster had been applied to the section.

Also discussed were the different techniques used by conservators today to remove frescoes from their original locations. (Three techniques are used, stacco a massello, stacco and strappo).

I have discovered that there are many videos on YouTube which explain fresco techniques used in different eras. This one below is specific to the era that this module covers and covers what we were told about fresco creation in medieval times. It is 17 minutes long, in Italian with English and French subtitles.

Oil painting also existed before the 1400s, in Flanders and in England. Linseed oil was used in the 13th century painting of the Westminster Abbey altarpiece.

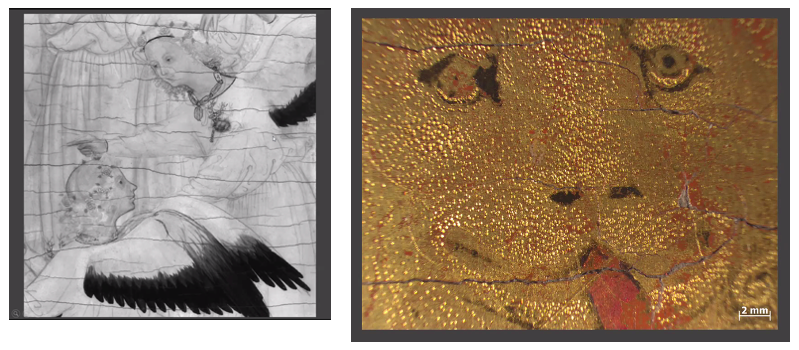

In the second half of this session, Rachel Billinge took us beneath the surface of The Wilton Diptych to explore what cannot be seen with the naked eye. This was magical to see.

The Khan Academy has produced an informative 6 minute video about this diptych, and we were given a lot of information about the diptych, how it was created (egg tempera on wood) and the symbolism within the diptych, which I do not have time or space to cover here.

But here are some of the wonderful images that Rachel Billinge has captured through her microscope.

As ever, there was far too much covered in this week to record here, but hopefully this gives a flavour of the wonderful content of this module.

Week 6: Women and society

Whilst this is Week 6 of Module 1 of the National Gallery’s Stories of Art Online course, as mentioned before I have already completed Modules 2 to 7. Through these 7 modules the National Gallery has noticeably tried to include reference to women artists and to artists of colour. This week was introduced by Siân Walters as follows:

“Studying the art of the period 1250-1400, we could be forgiven for thinking that nearly all works produced were commissioned and paid for by men. Yet in recent years, historians have found more evidence of women acting independently. In this session, we consider their roles. What kinds of women were able to transgress gender boundaries and commission works of art? How were women depicted in paintings of the period and what does this tell us about their place in society? We also examine representations of female saints and the iconography of the Virgin Mary.” (Text from Siân Walters’ handout.)

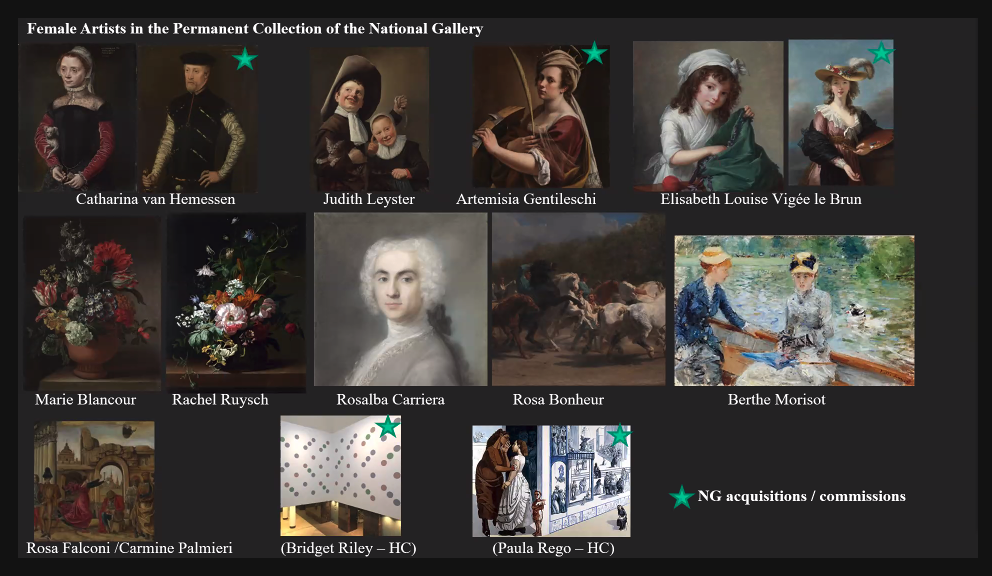

It seems that this effort by the National Gallery to increase its representation of women’s work is much needed. Currently less than 0.5% of paintings in the National Gallery are by women and there are only 12 pieces of work by women in the permanent collection that are on view.

In addition, a number of the works of art were not acquired by the National Gallery but were bequests. In the same vein, in 2018 Sotheby sold 1000+ works of art by male artists, but fewer than 15 by women. This is beginning to change but more needs to be done and more research into why this is the case is also needed.

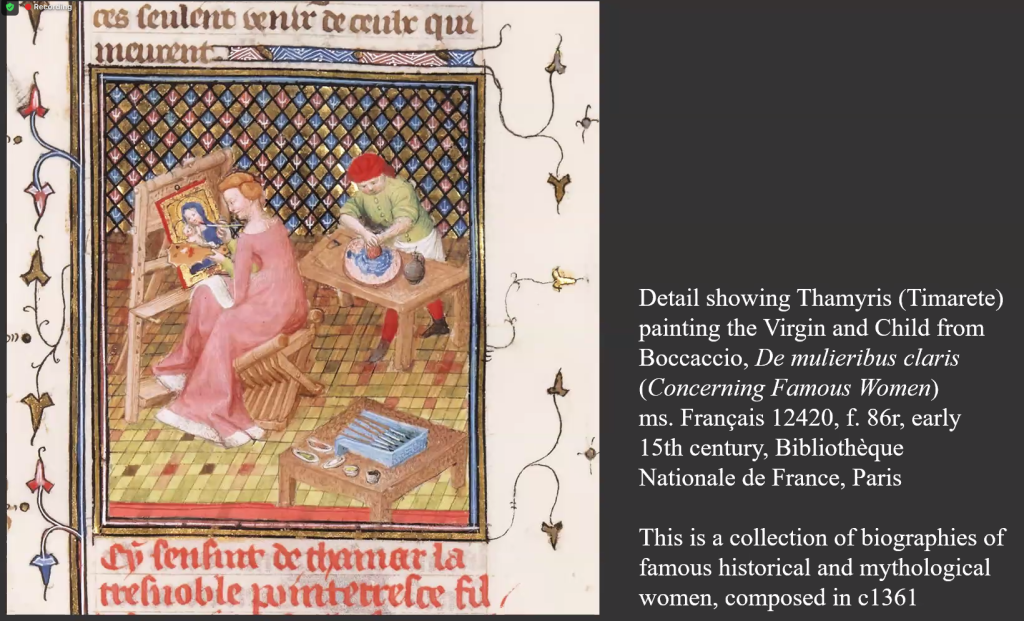

Despite the situation today, there is evidence that there were lots of women artists in medieval times. “In 1360, Boccaccio began work on De mulieribus claris, a book offering biographies of one hundred and six famous women, that he completed in 1374.” An example is seen in the painting below:

This work by Boccaccio and a closer look at medieval paintings shows that women at the time were a lot more independent than in later times and their roles were more varied. They were soldiers, builders, doctors, teachers, spinners, brewers, textile workers and guild members.

Women fighting to defend Castle, from Giovanni Boccaccio, Des cléres et noble femmes (Concerning Famous Women), Spencer Collection MS. 33, f.63v, French c. 1470, New York Public Library, New York

Women were also patrons. Can you see the patron depicted in the painting below, the small figure at the bottom right of the painting?

Anon Sienese artist, The Virgin and Child with donatrix Madonna Muccia, c.1320, Lucignano, Val di Chiana.

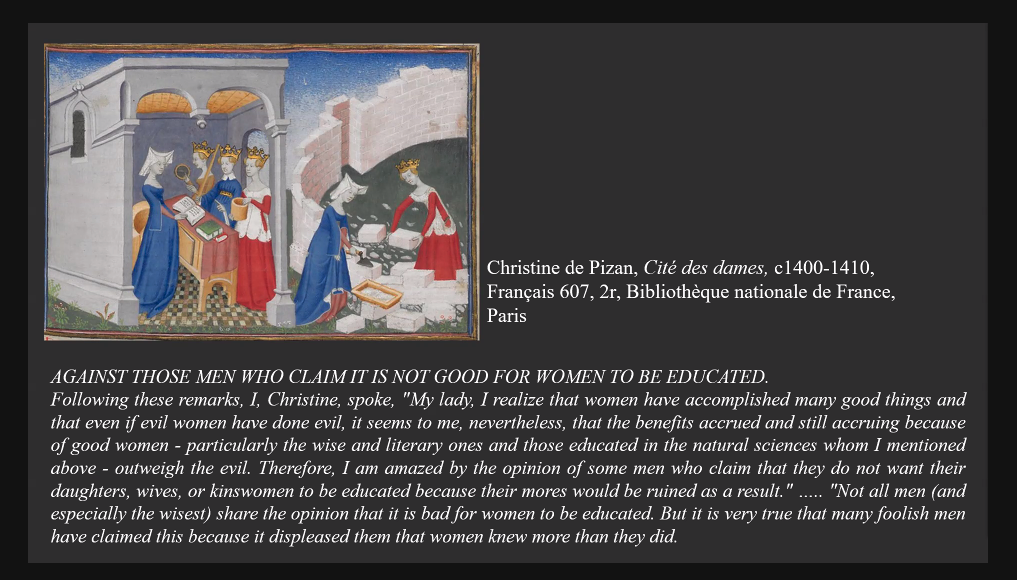

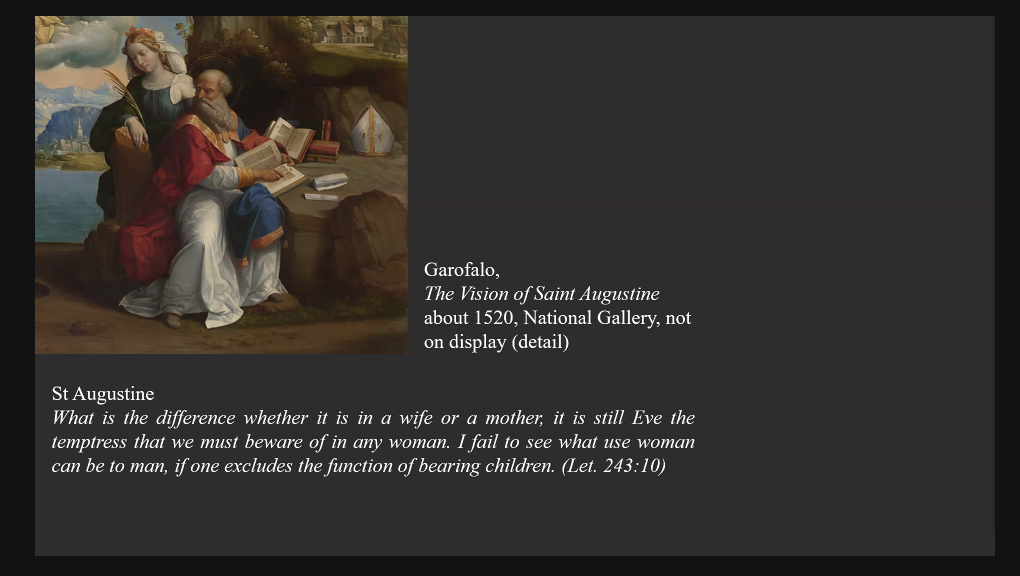

Despite all this, women still had to contend with criticism from men, and this criticism grew in Renaissance times which promoted a patriarchal society, pushing women out of the guilds and often depicting the Virgin Mary as a scarlet woman, and Eve as the source of all evil.

Once again, there was far more in this week’s content than I have space to report on here, particularly in relation to the iconography of the Virgin Mary and how she was represented during medieval times.

This is the final week in this module. It has been a surprise to me how much I enjoyed this module and how interesting I found it. I will now be much more likely to visit the sections of art galleries that have medieval work on display.