Module 5 of the National Gallery’s course, Stories of Art. A Modular Introduction to Art History, covered 18th century art. This six week online course was presented by Dr Richard Stemp, who wrote in his introductory handout:

The 18th century was an important period of change across Europe. The death of Louis XIV in France led to a relaxation in court life, which led to a far lighter touch in French art, and the development of Rococo.

(I have included lots of images in this post. Clicking on them enlarges them.)

Week 1: A lighter touch

Baroque art of the 17th century had suited the bold dramatic style of Louis XIV and his court in Versailles. With his death, and the ensuing regency, the court returned to Paris and became more relaxed. Two artists whose work flourished in this new lighter atmosphere were Jean–Antoine Watteau and William Hogarth.

Watteau was born at Valenciennes in the north of France and arrived in Paris in 1702 where he began to paint. He died in 1731 at the age of 36 from consumption. This lovely portrait of him, was painted by Rosalba Carriera (who was enormously popular in the 18th century and did wonderful work in pastels).

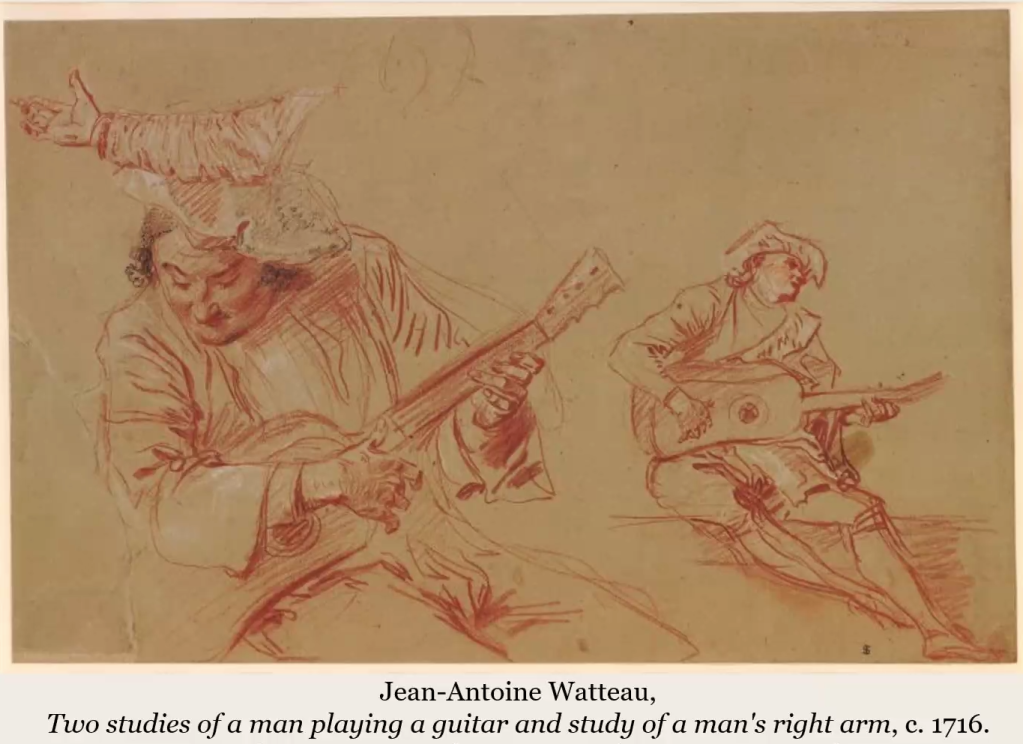

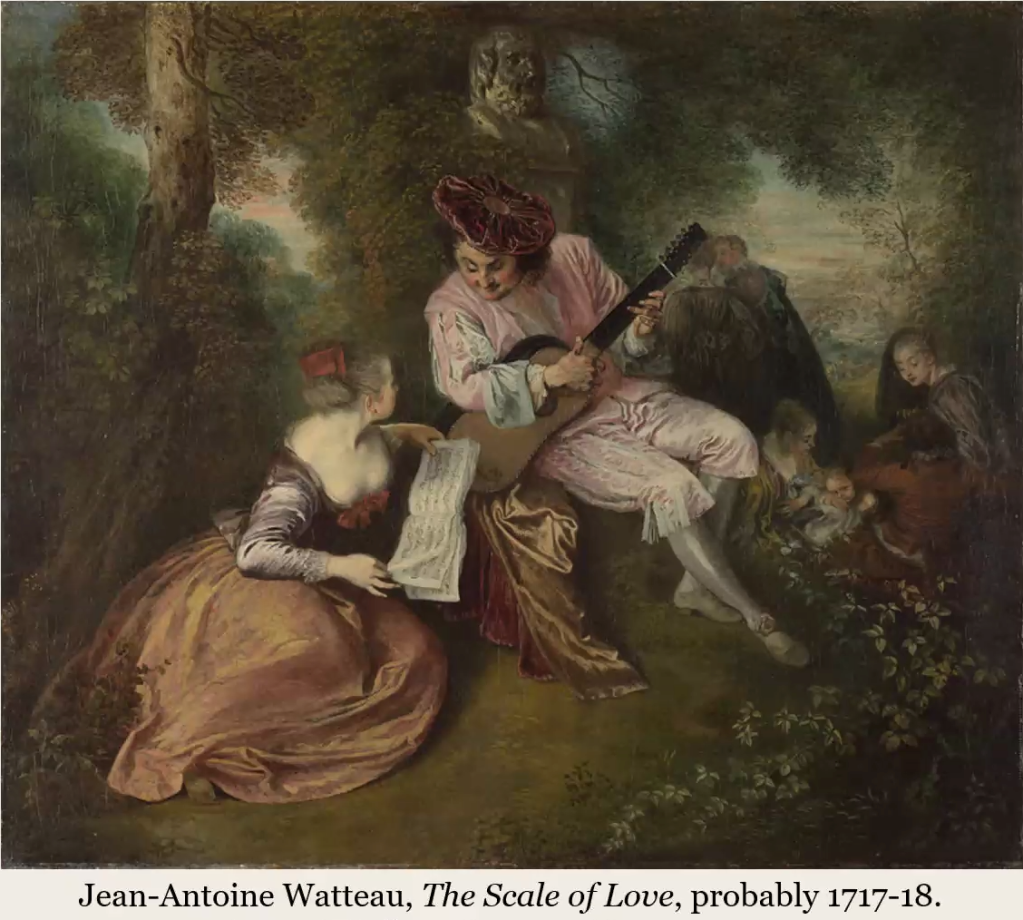

Watteau himself is considered one of the greatest of Rococo artists. His paintings were observations of society, normal people doing normal things. In the tradition of Rubens, he used red, white and black chalk for drawings, before he started to paint, creating hundreds of drawings which he used over and over again in his paintings.

E.H. Gombrich writes of Watteau, ‘The qualities of Watteau’s art, the delicacy of his brushwork and the refinement of his colour harmonies are not easily revealed in reproductions. His immensely sensitive paintings and drawings must really be seen and enjoyed in the original.’ I also think that it really helps to be able to zoom in on his paintings, which is an advantage of an online course.

In Week 1 we also examined in close detail Hogarth’s first series dedicated to ‘Modern Moral Subjects’, Marriage A-la-Mode.

Hogarth’s paintings exposed the follies and vices of the age. He was the finest and liveliest British portrait painter of the time, a man with a well-developed sense of cynical humour, and also an engraver, so he sold many prints of his work.

In Week 4 we were shown this painting, which illustrates his skill as a portrait painter.

Week 2: Defining the Rococo

In this week we were shown the work of a variety of artists of the period and at least 120 slides to explore the differences between Baroque and Rococo art. It seems that Rococo art is difficult to define. Some think that it’s not a style at all but a form of late Baroque, others that it is a style in its own right; it’s not what the baroque is. In his book Baroque and Rococo, Gauvin Alexander Bailey writes :

‘Baroque (c.1580-c.1700) grew out of the Catholic Reformation, and is a powerfully persuasive style based on rhetoric and drama, whereas Rococo (c.1700 – c.1800) began as décor, a whimsical, more intimate style that values ornamentation over structure and is more concerned with pastoral and exotic forms than with weighty theological or historical themes.’ (London: Phaidon, 2012)

Rococo art was described in this lecture as frilly, and joyful in its approach. Whereas Baroque art is bold and symmetrical, characteristics of Rococo art are asymmetry, and sinuous S-shaped scrolling curves. Rococo paintings were described as effervescent, gentle and elegant, employing soft, gentle colours and grounded in the world of imagination. An example of this is Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s The Swing. There couldn’t be a more Rococo painting than this.

This frothy, titillating painting is considered one of the quintessential works of Rococo art. Fragonard was influenced by the work of François Boucher and Giambattista Tiepolo.

Week 3: The Grand Tour

The 18th century was the time of the grand tour. Photography had not been invented so the best way to see European art was to travel to Europe, which many young gentlemen (known as ‘bear-cubs’) did, in the company of a tutor (the ‘bear-leader’), after studying at either Oxford or Cambridge (the only two Universities that existed at the time). These tours usually took about eighteen months, and of course they also served the purpose of ‘sowing wild oats’. The most common tour was to travel from England through France to Italy and down through Venice to Rome and Naples, but some ‘bear-cubs’ travelled further afield, and later in the century it became fashionable to travel to Wales, Scotland and the Lake District, no doubt attracted by the likes of Wordsworth and Coleridge.

And since there was no photography in this era, what better way to capture memories of the tour than by buying paintings, either of memorable sites and monuments, or of having your portrait painted in situ. Even Goethe had his portrait painted in Italy on his grand tour. So, at this time artists could make money by painting souvenirs. Notable amongst these artists was Canaletto, who is known for his many, many paintings of Venice. Typical of these paintings is The Basin of San Marco on Ascension Day.

To really appreciate Canaletto’s skill, visit the painting on the National Gallery’s website and zoom in, where you can see the extraordinary amount of detail in the painting and in his other paintings.

In this week’s session we saw many of Canaletto’s paintings of the Grand Canal in Venice and those which Canaletto painted of the Thames whilst living in England. We also saw how Canaletto’s work influenced other artists and architecture of the time, but we didn’t discuss this lovely painting (below) of The Stonemason’s Yard, although we were recommended (as homework) to watch a really interesting video of Associate Curator Francesca Whitlum-Cooper giving a talk about this painting – https://youtu.be/03BfPn6xrSo

I think I prefer this painting to the canal paintings. Maybe because there are so many Canaletto paintings of the Grand Canal in Venice. There are even two in the Bowes Museum in County Durham, not so far from where I live.

Week 4: Crossing Genres

Part 1: A New Face for Portraiture

The first half of this week’s two hour session was presented by Richard Stemp, who discussed the new face of British Portraiture in the 18th century. He focussed on three artists, Thomas Gainsborough, William Hogarth and George Stubbs. Gainsborough combined portraiture and landscape painting; portraits made more money than landscapes, so many landscape artists turned to portraiture. Gainsborough’s famous painting Mr and Mrs Andrews, is an example of this, and also an example of a conversation piece, a type of painting that became popular at this time and depicted an informal group portrait in which people are gathered together and involved in real or imagined activity. The National Gallery has a very entertaining video on its site of a variety of people discussing this painting – https://youtu.be/g_w–aEYmH8 Hogarth also painted a number of conversation pieces, as did Stubbs, but in the case of Stubbs the portraits were often of animals (particularly horses) as well as people, set in landscapes and depicting a narrative.

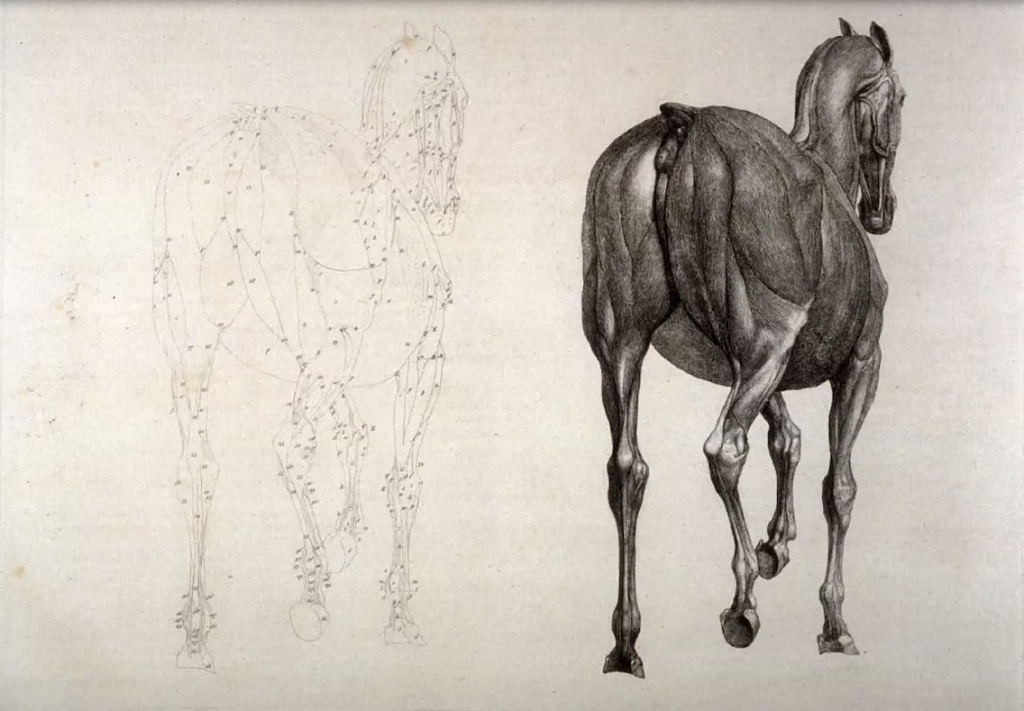

Stubbs studied the anatomy of horses, dissecting them and making many anatomical drawings which he later used to inform his paintings.

Part 2: Dido Elizabeth Lindsay Belle (1761-1804) and the Beginnings of Abolition

The second half of this session was presented by Leslie Primo, who traced the beginnings of abolition through the eyes of Dido Elizabeth Belle, a black woman living in Kenwood House in the late 18th century. Through looking closely at her portrait by David Martin, and other art work of the time, we observed the emphasis in 18th century art on white skin superiority, and considered how Dido was depicted as an exotic other, and what her life might have been like.

Week 5: Taking things seriously – Academies and Enlightenment

In the first half of this week’s two-hour session, Richard Stemp discussed how during the 18th century art was changing, from the ‘lighter touch’ of the Rococo period, to the more serious period of the Enlightenment (the Age of Reason), focussing on advances in science and philosophy. This was illustrated by discussion of Joseph Wright of Derby’s painting An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, which depicts a scientist conducting an experiment during which a vacuum is created by the air pump, which for a moment robs the bird of the air it needs in order to breathe. The people in this painting are ‘being enlightened’ and their faces are lit up.

Richard Stemp then went on to discuss some of the great thinkers so of the age; Mary Wollstonecraft, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Denis Diderot (who published the first encyclopaedia and became one of the first art critics), Voltaire, Goethe, Johann Joachim Winckelmann and Edmund Burke. These thinkers encouraged artists to take art more seriously, which led to the founding of the British Royal Academy, depicted here by Johan Zoffany.

Artists working at this time included Francisco Goya, François Boucher, Jean-Baptiste Greuze, Jean-Simeon Chardin, William Gilpin, Joshua Reynolds, Angelica Kauffmann and Mary Moser. As women, Kauffmann and Moser did not attend the academy, although Kauffmann was one of the most successful artists of the time and hugely wealthy; their portraits are displayed on the wall.

The second half of this week’s session was led by Dr Jenny Graham, Associate Professor (Reader) in Art History at the University of Plymouth, who spoke on the cult of sensibility and changing representations of masculinity in 18th century art, with reference to the paintings of Reynolds, Gainsborough, Chardin, Boucher and Greuze. We were shown a wide range of portraits showing the shift from portraits of men of power, very often symbolised by the white stockinged masculine calf, to softer representations of men of feeling, surrounded by nature, or depicted as loving husbands and tender fathers, often seated amongst their family. These two portraits below by Reynolds and Gainsborough, which have taken similar subjects, show the shift from Reynolds’ benchmark portrait of machismo, to Gainsborough’s pensive officer, lost in thought.

Week 6. Neo-Classicism: From Revolution to Empire

Richard Stemp introduced this module as follows:

Changes in artistic style are the result of many overlapping ideas – political, historical and theoretical. From the Renaissance onwards, an interest in the antique had been one of the major forces behind artistic style, but the focus had always been on ‘Rome’ as the highpoint of classical civilization. In 1764, Johann Joachim Winckelmann’s History of Ancient Art was one of the first books to distinguish between the arts of Greece and Rome, and to identify the primacy of the Greeks. At this point, the ‘Neo-Classical’ was born – the perfect antidote to the apparent superficiality of the Rococo. It became the perfect language for French revolutionaries to express the earnestness of their beliefs about the decadent monarchy, and an ideal form of expression of dignified intent for the revolutionary turned Emperor, Napoleon Bonaparte.

There was far too much information packed into this week to cover in this very short reference to Week 6 of this module. Neo-Classical art was described as rational rather than emotional, with its origins in Greek sculpture. Neo-Classical art exhibits noble simplicity and quiet grandeur. It is cool, calm and sophisticated, with sculptures being white and paintings worked in subdued colours. Richard Stemp said, Baroque is like dark chocolate; Neo-Classicism is like spearmint, and Baroque is like full fat cream; Neo-Classicism is like skimmed milk. Many artists were referred to in this session. Here are some which exemplify Neo-Classical art.

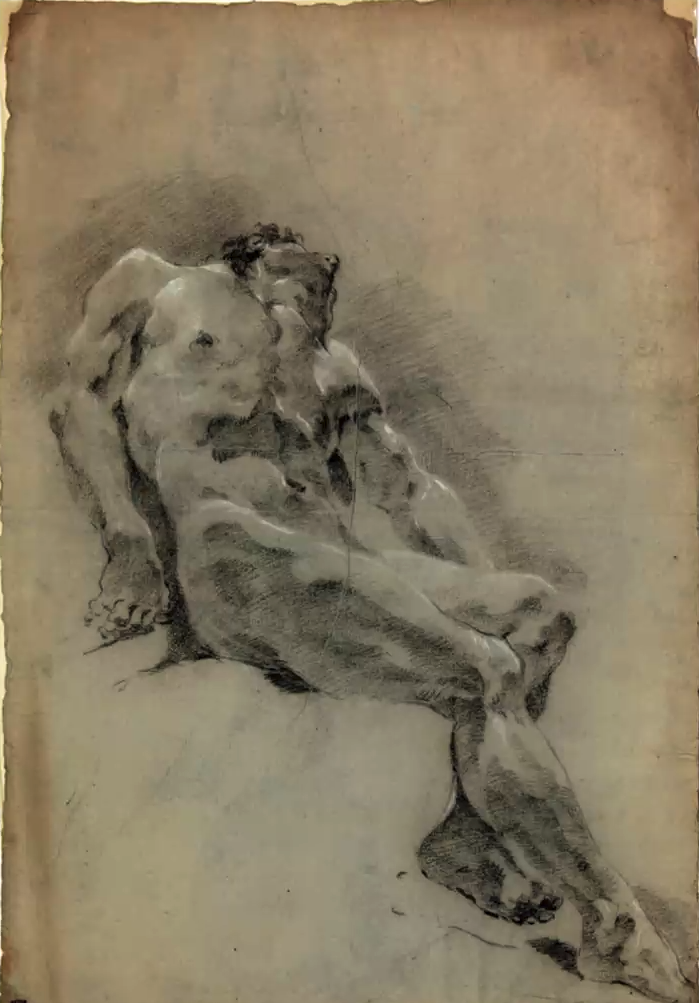

And these wonderful male nudes by Giulia Lama (1720-23). Most women artists at this time worked from sculptures rather than directly from the male model, but Giulia Lama broke with the convention of the time.

Module 6 will be led by Dr Amy Mechowski and will look at 19th century art (1800-1900).

It will start on June 2nd 2021

https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/events/course-stories-of-art-online-module-6-1800-1900-2021