Last week I completed the fourth module of the National Gallery’s six week online course – Stories of Art: A Modular Introduction to Art History, 1600 -1700. The title of this module, hosted by Lucrezia Walker, was Baroque and the Dutch Golden Age. I really enjoyed this module, probably because of the amazing artists discussed – Bernini, Caravaggio, Artemisia Gentileschi, Rubens, Poussin, Velázquez, Rembrandt and Vermeer.

What I didn’t know before starting this module is that the word ‘baroque’ derives from the Portuguese ‘barroco’ word, which describes a large, irregularly shaped pearl. In relation to art, this was originally a derogatory term, suggesting excess, a flamboyant response to Renaissance classicism. Baroque was the leading style of this period.

As for previous modules, the course covered a wide range of artists, and showed hundreds of slides. There were 70 slides in Week 1 alone. For this post I will select one or two images from each week, to share a flavour of what the course was like.

Week 1: The power and the glory

The focus in Week 1 was on the power and glory of 17th century Rome and in particular the wonderful sculptures of Gian Lorenzo Bernini, described by Lucrezia Walker, as the ‘big boy of Baroque’, an extraordinary tour de force. Bernini’s father was a sculptor, so Bernini began his learning at the age of eight, to ultimately become the Michelangelo of Baroque, a giant figure of many talents – sculptor, architect, painter, playwright, theatre designer and musician. He has been described as the ‘artistic dictator of Rome’. Bernini worked on St Peter’s Basilica for 40 years, and was so talented that he could make marble look like flesh, as you can see from this photo below of his sculpture of The Rape of Proserpina.

Not only did we get a great introduction to Bernini in the first half of Week 1, but we were also given a good look around the sites of Rome where his work features.

The second half of Week 1 was devoted to the art collection of King Charles 1, which was unprecedented in England. This collection was an indication of his power and glory. He collected work by Van Dyck, Titian, Rubens, Holbein, Bronzino and Mantegna.

Week 2: Caravaggio, the Catholic Reformation and the beginnings of Baroque

This week focussed on the first half of the 17th century in Rome, and in particular on the work of Caravaggio, in the first half of the session, and Artemisia Gentileschi in the second half. Both Caravaggio and Artemisia were hugely influential in the early 1600s, and then became less important, and were not rediscovered until the late 20th century (Caravaggio) and 21st century (Artemisia).

Caravaggio had a violent temperament, characterised by drinking, brawling, gambling and fighting. In 1606 he had to flee Rome after killing a man and spent the rest of his life travelling between Naples, Malta and Sicily. He was constantly in trouble, but he was hugely influential. His style was innovative and naturalistic, with dramatic contrast of light and dark. It formed a new kind of art for a new catholic church, and from about 1600 onwards, Caravaggio never wanted for patrons. Because Caravaggio produced a lot of work for churches, his work was widely viewed, more so than if he had painted solely for private collectors.

Artemisia was the most celebrated female painter of the 17th century. Her mother died when she was twelve and being the eldest child of a family of daughters she worked in her father’s studio, producing professional work by the age of 15. As a young woman, aged 17, Artemisia was raped by Agostino Tassi, an artist who visited her father’s studio. He was convicted of rape in 1612, but this event influenced not only Artemisia’s work, but also how her work was perceived. Nevertheless she became a successful court painter in Florence. Artemisia was strongly influenced by Caravaggio; her paintings were highly naturalistic.

Her painting, in 1610, of Susanna and the Elders (image above), which she painted at the age of 17, shows her distinctive style and was surely a premonition of what was to befall her within a year of painting it. But Artemisia has become a heroine of feminist art history. ‘I will show Your Illustrious Lordship what a woman can do,’ she wrote to a Sicilian patron. ‘You will find the spirit of Caesar in the soul of a woman.’

Week 3: The embarrassment of riches: Painting in the Dutch Republic (not baroque)

I found this the most stimulating all the six weeks. In preparation (as homework) we were asked to watch Rembrandt vs Vermeer on Intelligence Squared – https://youtu.be/cCQZnXz2Uss. This is a highly entertaining programme which I can recommend. Tim Marlow chairs a debate between Simon Schama and Tracy Chevalier over who is better, Rembrandt or Vermeer? This reminded me of a wonderful trip to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam in 2014, where I saw paintings by both Rembrandt and Vermeer.

At the beginning of this week’s session we were asked to vote on whether we preferred Rembrandt or Vermeer. The result of the poll was exactly 43% to each, with the remainder being ‘no preference’ responses. I voted for Rembrandt, which I probably wouldn’t have done if I hadn’t been to the Rijksmuseum, but as one participant said, it’s like comparing apples and pears.

Rembrandt was the 9th child of a wealthy miller and had a classical education. He was married twice (his wives feature in his paintings), lived to the age of 63, and was successful in his lifetime with a large studio. He produced a huge amount of work, including 80 self-portraits. He was a great painter of humanity.

Rembrandt, Portrait of Aechje Claesdr, 1634

Vermeer, a tavern owner and a dealer, as well as a painter, lived a shorter life, dying at the age of 42 . He was a much quieter artist than Rembrandt, painting simple images of glorious ordinariness. He produced relatively few paintings, working slowly and producing a couple of paintings a year. Vermeer painted scenes from everyday life, often a single figure in a room with light from the left. It is thought that he may have used a camera obscura, and he is known for lavish use of the expensive pigment lapis lazuli.

Vermeer, Woman pouring milk, c1658

Between 1640 and 1660, Amsterdam was the place to be, clean, ordered, with impressive land reclamation projects (God made the world, except for Holland, which the Dutch made!). There were more painters than butchers in Amsterdam and an explosion of different genres of painting, portraits, landscapes (townscapes, seascapes, urban landscapes, winter scenes) and still-life (lavish still-life and the vanitas still-life); ordinary people were buying art. This was the era of the rise of the dealer and the beginning of the art market. This was also a time when artists worked collaboratively on paintings. Some of the other painters introduced this week were Gerrit Berckheyde, Peter Saenredam (so different from Italian paintings of Catholic Church interiors ), Willem Kalf, Jan Janz Treck, Harmen Steenwyck, Adrien van Utrecht, Rachel Ruysch (whose paintings sold for more than those of Rembrandt‘s at the time), Willem van Aelst, Jacob van Walscappelle (still life), Aelbert Cuyp (landscape), Judith Leyster (portraits) and Pieter de Hooch.

Week 4: The art of Spain

Significant artists working in Spain in the 17th century included El Greco, Zurburan, Velázquez and Murillo. For the first half of this week’s session we looked at the work of all these artists. The second half of the session focussed on Diego Velázquez, whose work was discussed in more depth by Dr Gabriele Finaldi, Director of the National Gallery.

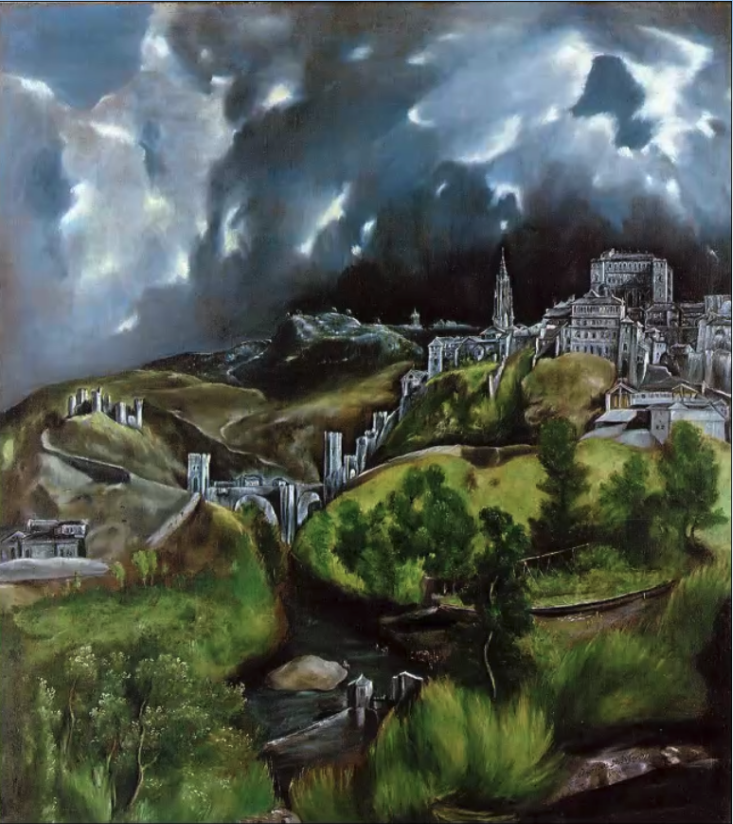

El Greco’s work took me by surprise. It seems so modern, and his influence can be seen in both cubism and expressionism. El Greco was a one off. He doesn’t seem to fit in any art school. His style was highly individual to the extent that people wondered whether he had a problem with his eyesight. His work is other worldly. He often elongated or over exaggerated his subject and used unusual colour effects. El Greco was born in Crete, but he travelled to Venice and Rome, before finally moving to Toledo, which was the capital of Spain until 1560. He was influenced by Titian, but particularly by Tintoretto.

El Greco, View of Toledo, 1596-1600

Velázquez was born into an educated literary family (a Portuguese mother and Spanish father) in Seville. but ultimately moved to Madrid where he spent his entire career in the service of King Philip IV, who was a sophisticated admirer of art. Velázquez was a famous painter at court, knighted by the King, with the Order of Santiago, and twice sent to Italy, which played an important role in shaping his art, where he came under the influence of Titian’s work. Las Meninas is thought to be Velázquez’ masterpiece.

Velázquez, Las Meninas, 1656

The painting doesn’t particularly appeal to me, but Dr Gabriele Finaldi, gave a very plausible explanation of why it has become such a revered work of art. It is a large group portrait which includes Velázquez himself with the cross of the Order of Santiago on his chest and the King’s daughter. The painting is a fascinating paradox of what is shown, and what isn’t; what is said and what isn’t; what is real and what is not; a story within a story; an image within an image. Las Meninas is a manifesto for painting. It shows that for Velázquez, painting is a speculative activity, not simply mechanical.

Velázquez is also known for The Rokeby Venus, which was famously attacked and badly damaged in 1914 by the suffragette Mary Richardson, although later restored.

Week 5: Rubens and Van Dyck (Flemish art)

This week the focus was almost entirely on Rubens and Van Dyck, Rubens’ pupil. The first half of the session provided an introduction to both painters by Lucrezia Walker, and the second by Dr Chantal Brotherton-Ratcliffe, who explored the work and skill of both artists in more depth, showing us how to recognise the difference between these two artists by their brush strokes.

Rubens was described as the most successful artist who ever lived. He was extraordinarily important as a painter and was knighted by both Charles I of England and Philip IV of Spain. He was charming, and not only a painter, but also a polyglot, businessman and diplomat. Rubens had a very happy private life, marrying 16 year old Isabella Brandt at the age of 32, and after she died marrying another 16 year old, Hélène Fourment, at the age of 53. From Antwerp, Rubens visited Rome, where he saw the work of Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael and Caravaggio, who all influenced his work. As a painter Rubens was prolific. He had a studio of about 50 assistants and was therefore able to take on large commissions and deliver them quickly. On some paintings he collaborated with Jan Brueghel the Elder who painted the backgrounds. Rubens also painted landscapes but he was known more for his paintings of fulsome women.

Rubens, Le Chapeau de Paille, 1622-25

He was strongly influenced by the work of Titian, and like Titian used thick paint on a heavily-laden brush, which gave his work a 3-dimensional sculptural feel. He loved strong colour, particularly vermillion. Later in his career, like Titian, he began to experiment with ‘less is more’, a softer, non-specific way of painting and used thinner paint.

Van Dyck was Rubens’ best pupil, very precocious and almost like a post-grad student, to the extent that it was sometimes difficult to tell their work apart. He was born to prosperous parents in Antwerp and by the age of 15 was already an accomplished artist. His father was a silk merchant, so Van Dyck was excited by fabrics, which can be seen in his paintings. Van Dyck spent most of his life working in Spain and England, where he became the leading court painter and was knighted by King Charles I, but he also visited Italy. Like Rubens he was heavily influenced by the work of Titian, and owned 19 Titians by the time he died. Van Dyck was known for his portraits.

Van Dyck, Charles I in Three Positions, 1635 or 1636

Van Dyck died at the age of 41 by which time he was painting with thinner and thinner paint to the point where the ground paint showed through.

Week 6: Dreaming in Rome

In this final week the focus was on two important French artists working in Rome in the 17th century: Claude Lorrain (commonly known as just Claude) and Nicolas Poussin. Both these artists influenced future generations of painters. The influence of Poussin can be seen in the work of Benjamin West, David, Ingres, Delacroix, Cezanne and Picasso. The influence of Claude on Constable and particularly Turner is easily seen, to the extent that Turner, in his will, requested that the National Gallery hang two of his paintings next to two of Claude’s.

In the 17th century Rome was being revivified. The city was in ruins, but was full of vestiges of a great lost past, which artists found charming and poetic.

At this time the Cardinals were amassing art collections and there were many Papal commissions. This drew Poussin from Normandy to Rome in 1624 at the age of 30, when Rome was entering its full baroque period under Bernini. Poussin’s early work depicted mythological scenes and historical narratives, but later in his career he began to paint landscapes.

Poussin, Landscape with a Calm, 1651

Claude also finally ended up in Rome in 1628, where he too worked on landscapes, going out to paint with his friend Poussin. Both artists constructed their landscapes to lead the eye back through the paintings.

Claude, A Sea Port, 1639

Next week will see the start of Module 5 in this art history course, and will explore the 18th century (1700-1800), looking at the art of Fragonard, Watteau, David, Hogarth, Gainsborough, Stubbs and others.