In this fascinating discussion on Forum for Philosophy, Adrian Holme, Milena Ivanova and Jonathan Birch discussed questions surrounding the nature of beauty, and the role of beauty in the relationship between science and art.

Jonathan Birch, the host, started the discussion by posing the following questions: We know that nature inspires art, but can abstract science inspire art? What counts as beautiful science? What’s the significance of beauty in science? Is beauty a guide to truth?

In response Adrian Holme showed us some examples of where science has inspired art. The first example was Joseph Wright of Derby’s, An Experiment on a Bird in an Air Pump, 1768, where the process of science, the experiment, was the inspiration for the painting.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:An_Experiment_on_a_Bird_in_an_Air_Pump_by_Joseph_Wright_of_Derby,_1768.jpg

In this painting we see the fearsome power of science to destroy the objects it investigates. Air is being sucked from the glass chamber. The bird in the chamber is dying. The painting also shows that both art and science are public activities which require an audience.

Then, when Adrian showed us an image of The Shah Mosque in Isfahan, the discussion turned to the role of mathematics and in particular, geometry, in unpicking the relationship between art and science.

https://www.tappersia.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Shah-Mosque-5-Isfahan-TAPPersia-1.jpg

In the past, sculptors had to have a good understanding of mathematics and there was always a correlation between art history, science, mathematics and geometry. In the time of Leonardo da Vinci there was not a great conceptual divide between art and science. Both required knowledge and skill. In relation to this image, Adrian made the interesting comment that pattern runs deep into who we are.

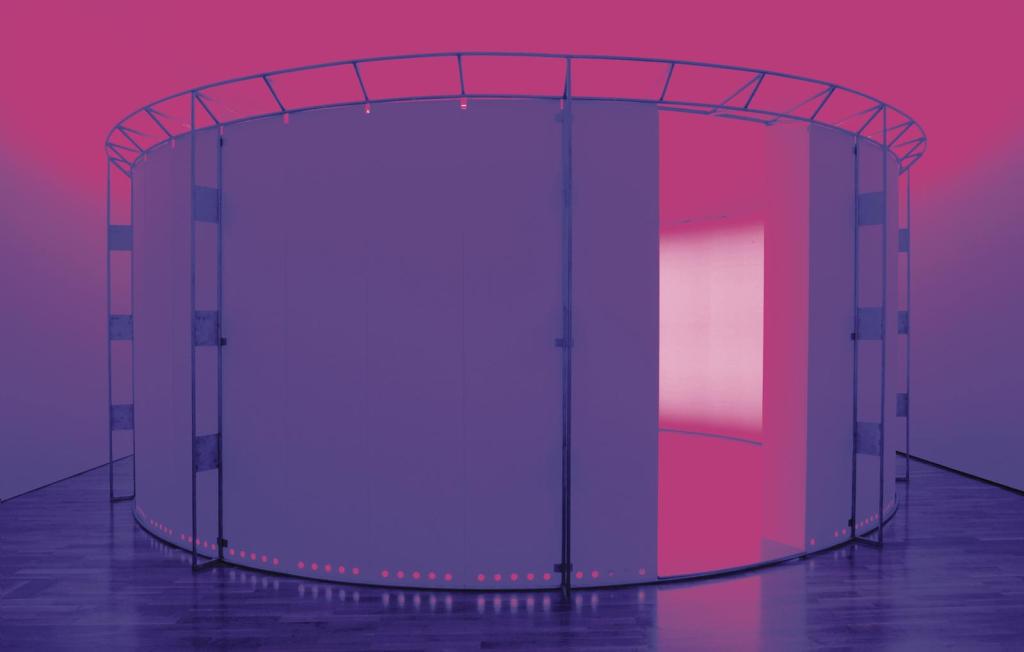

The third image was of Olafur Eliasson’s 360o Room for All Colours 2002

https://olafureliasson.net/archive/artwork/WEK101068/360degree-room-for-all-colours

This is an installation which consists of a circular space that surrounds visitors with slowly changing colours. It is a scientific experiment on our optical experience, but is also aesthetically pleasing. It plays with our perceptions of vision and is disorienting. Eliasson is interested in the ways in which people respond. Like Joseph Wright of Derby’s painting, this art works at the interplay between pleasure and discomfort. This installation raises the question of whether art can actually be science.

A member of the audience then raised the question of whether art would have the same appeal if it were created by machines, algorithmically. Adrian thought it might, although he thought that machines will create art better and quicker, but that the art would be banal. However, Milena Ivanova said that she had seen art created by artificial intelligence that she could not distinguish from art not created by machines. This raised the question of whether machines can be conscious and have their own subjective points of view or are they just mimicking humans? Milena pointed out that machines can create their own algorithms, but these questions related to artificial intelligence and consciousness were clearly straying away from the topic of the nature of beauty. Jonathan Birch, as host, then pulled the discussion back to the question of whether there is a definition of what art is and can a scientific experiment be an art work? Adrian Holme thought that some might be, if we think of scientific experiments as a performance.

The discussion up to this point was led mostly by Adrian, who drew on his experience as an artist to consider what science has done and can do for art. The second part of the discussion focussed on what art can do for science and whether science can be beautiful. These are ideas that Milena has recently been researching. At the beginning of this year she published a book with Steven French – The Aesthetics of Science. Beauty, Imagination and Understanding. She was very knowledgeable about this topic and had a number of interesting points to make, but she talked very fast and was sometimes difficult to follow. Hopefully there will be a recording of the discussion.

Here are some of the points I captured during this second part of the discussion.

Scientific phenomena can be beautiful, but what does it mean to know this? Scientists tell us to trust theories, without the evidence, because they are beautiful, and there is evidence that theories have been accepted on the basis of their beauty. Science can be motivated by the idea and search for beauty. There are aesthetic claims for theories of physics. How can we justify aesthetic judgements?

There seem to be some constant values which people use to make judgements about beauty and what is beautiful in science, e.g. simplicity, symmetry, elegance, naturalness, unity. These are some of the values that seem to be uniformly understood by different communities as related to beauty in science. But Milena noted that standards of beauty change over time, and sometimes there is resistance to this change, for example the beauty of the shape of an ellipse as opposed to a circle; this change occurred with changing understanding of the earth’s orbit round the sun. Here Milena referred to James McAllister’s work on Beauty and Revolution in Science. McAllister questioned how reasonable and rational can science be when its practitioners speak of ‘revolutions’ in their thinking and extol certain theories for their ‘beauty’. He studied the interconnection between empirical performance, beauty, and revolution.

Milena also referred to Sabine Hossenfelder, author of Lost in Math: How Beauty Leads Physics Astray, who has argued that an obsession with beauty has led physics astray. ‘Why should the laws of nature care what I find beautiful?’ Hossenfelder asks. ‘The more I try to understand my colleagues’ reliance on beauty, the less sense it makes to me.’ This suggests that science is not always about truth.

So is there a single concept of beauty for different realms? Do biologists have the same concept of beauty as physicists? Philosophers and scientists believe we should trust in beauty, but if science is not always about truth, what is the relationship of beauty to understanding and truth? Milena believes that beautiful ideas, simple and elegant, are easier to work with. Maybe it’s not necessary to obsess about truth.

The introductory material for this discussion included the following questions:

When presented with two equally good theories, scientists often prefer the more beautiful. Does this mean that more beautiful theories are also more likely to be true? That, as Keats wrote, beauty is truth, and truth beauty? Does this tell us anything about the nature of reality? And what does this mean for science and art and how they inform one another? We discuss the nature of beauty and reflect on the symbiotic relationship between art and science.

Whilst very enjoyable and interesting, it seemed to me that only the last two questions were discussed and even then it was impossible to come to a conclusion. A definition of beauty, art or truth remains open to question. But there seemed to be agreement that art and science influence each other. There does seem to be a symbiotic relationship between them and both aim for beauty whether or not we can articulate its nature.