Module 6, the penultimate module of the National Gallery’s course, Stories of Art. A Modular Introduction to Art History, covered 19th century art. The module was presented by Dr Amy Mechowski, and during the six week course, three of the sessions featured an in-depth contribution from guest speakers, who presented the second hour of the two hour weekly session. In this first week, the guest speaker was Dr Susanna Avery-Quash

The 19th century was an age of unprecedented cultural, political, and social change. This module explored how this period of change was manifested in works of art. It also paid particular attention to paintings in the National Gallery and the work of the National Gallery, since it was in the 19th century that the National Gallery was established.

This has been a difficult module to reflect on in one blog post. It was so packed with information and images that it has been hard to know what to include. It was also quite hard to follow, simply because of the sheer weight of content. I sometimes think less might be more.

Week1: A New Age and a New Gallery

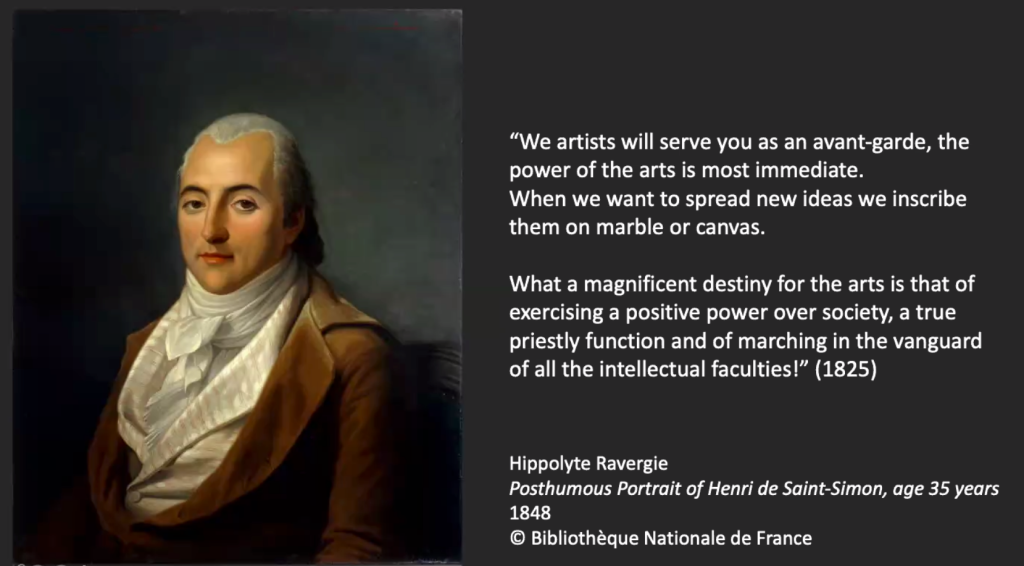

In this first week Amy Mechowski didn’t focus on particular artists, rather she gave us an overview of the influences of the long 19th century on art and artists. The long 19th century is a term coined by Russian literary critic and author Ilya Ehrenburg, and British Marxist historian and author Eric Hobsbawm, for the 125-year period comprising the years from 1789 to 1914. This period included the avant-garde in the first half of the 19th century and the start of modernism in the late 19th century/early 20th century. The avant-garde was a pathfinding force, characterised by unaccepted change, when artists were leaders alongside scientists and other change makers.

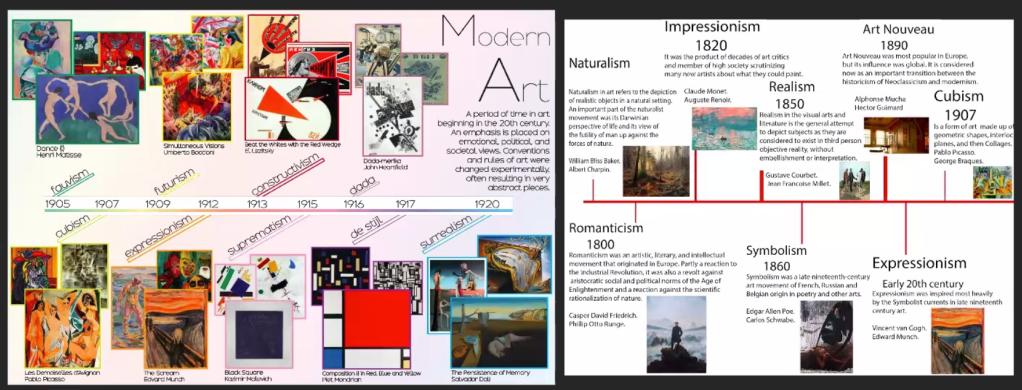

There remains debate about when modernism started – was it 1900 with fauvism, or 1800 with Romanticism, or 1850 with realism? The 19th century was an era of ‘isms’!

The great events that influenced art of the 19th century were the French Revolution, the Industrial Revolution and those leading up to the First World War. The spirit of revolution marked this century. This was the century of The Great Exhibition, and the development of photography, a century characterised by contradiction between modernity and tradition, urban and rural life, and popular and high class. There were also issues around gender and social class, and these boundaries between the social classes were explored by artists such as Degas. What was appropriate for the working classes? Should they too visit museums, as the middle class were beginning to do? There were also issues around freedoms, equality and representations.

These issues were all reflected in the collections of the National Gallery which was finally established in 1824 through the efforts of Lord Liverpool, Charles Long and Sir George Beaumont. Prior to this art was only seen in private collections or occasionally in museums. The presentation in the second half of this week by Susanna Avery-Quash, focussed on the first director of the National Gallery, Charles Eastlake, and how through his work, and extensive travel abroad to see and collect art, he managed to change the direction of the National Gallery’s art collection and introduce a new acquisition policy that would extend and diversify the collection.

Week 2: Academies and Rivalries

In this week Amy Mechowski gave two lectures. For the first hour she focussed on The Academy: Neoclassicism and Romanticism. In the early 19th century academic art looked to classical art for inspiration. History painting (classical history and mythology) was at the top of the hierarchy of importance, followed by portraiture, genre painting, landscape and cityscapes, animal painting and finally still life. Neoclassicism was driven by The Enlightenment and the practice of going on Grand Tours as artists became familiar with the work of the Greeks and Romans. Neoclassical art is characterised by simplicity and sedate grandeur, austere clarity, moral truth and political purpose. Amy Mechowski put forward Jacques-Louis David’s work as the best example of Neoclassicism, and Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, a student of David’s, as the high priest of Neoclassicism. Ingres was a superb draughtsman and master of drapery and texture as we can see from this painting of Madame Moitessier, which took 12 years to complete and underwent several revisions.

Notable in Ingre’s work is how he played with composition, making many preparatory drawings, how he often painted women in front of mirrors, and the rubbery quality to his painting of flesh as can be seen in Madame Moitessier’s right hand. There is quite a story behind this painting which you can listen to on the video on the National Gallery’s website. See https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/jean-auguste-dominique-ingres-madame-moitessier

This first hour ended with a short discussion about the work of women artists (Annie Louisa Swynnerton, Laura Herford, Angelica Kauffman, Adelaide Labille-Guiard) and sculptors at this time (Anne Seymour Damer, Harriet Goodhue Hosmer, Edmonia Lewis), and their struggle to be recognised as professionals capable of engaging with methods and materials that were regarded as otherwise too dangerous, messy and generally prohibitive for women.

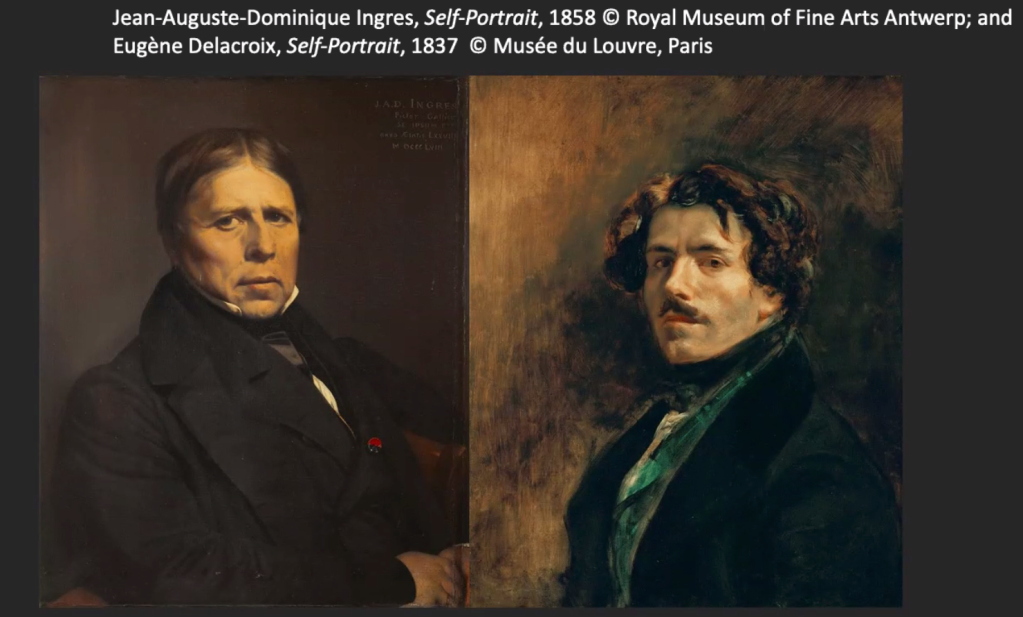

In the second hour, Amy Mechowski focussed on Romanticism and Rivalries, referring back to the rivalry between Ingres (Neoclassicism) and Delacroix (Romanticism), mentioned in the first hour ….

…. and then focussing on the rivalry between Turner and Constable in the period of Romanticism.

Delacroix was considered the greatest French Romantic painter. In comparison to Ingres, his work was loose, non-conformist, sketchy and expressive. These two artists showed the conflict between head and heart, the Neoclassicist Ingres’ paintings being dignified, restrained and balanced, and the Romanticist Delacroix’s paintings being passionate, rich and fiery in comparison. Romanticism was a response to disillusionment with the Age of Reason. It centred on imagination and emotion, the nature of man, and nature itself as unpredictable and violent, rather than ordered.

Landscape was a favoured subject for Romantic artists, as we see in the work of Turner and Constable, two very different artists, from very different backgrounds, who produced very different work. There was great rivalry between Turner and Constable which was depicted in Mike Leigh’s film Mr Turner (2014) which dramatized the moment that Turner and Constable clashed over two of the paintings they submitted to the Exhibition in 1832.

Both artists had radically new approaches to painting and the use of paint, which are discussed in some of the National Gallery’s videos. Watch Colin Wiggins give an entertaining, informative and in-depth talk on The Hay Wain (1821) in this video – https://youtu.be/aJVLyuk2cxI and Christina Bradstreet talk about Turner’s ‘Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway’ (1844) in this video – https://youtu.be/N8mf9y6ziXA

Week 3: Realism, Naturalism and Representation

As mentioned before, this module is proving difficult to capture in brief weekly notes. Dr Amy Mechowski has chosen to take a themed approach to each week, rather than focus on a particular artist. This seems to work against my purposes of making a record of each week in a brief paragraph, so these notes are shared on the understanding that they only present a fraction of what was presented, but even so this post is going to be very long!

In the first half of this week’s session, Amy Mechowski discussed realism and naturalism in 19th century art with particular attention to the work of Gustave Courbet and Jean-Francois Millet, in France, as well as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in England. These artists moved away from the traditional, classical and romanticist approaches of the past, to representing things closer to the ways we see them, often painting landscapes and other scenes from life out-of-doors (naturalism) and painting everyday life in a realistic, almost photographic way. Naturalism and realism took many forms, but often had a political edge, commenting on, for example, people working the land, through direct observation of the modern world.

Courbet’s paintings were rejected by the Palace of Fine Arts, but this didn’t deter him. He instead set up his own one-man independent exhibition, establishing himself as a Realist.

Similarly Millet’s honest depiction of rural poverty, made the upper classes uncomfortable and caused a scandal. Millet’s subjects were considered subversive.

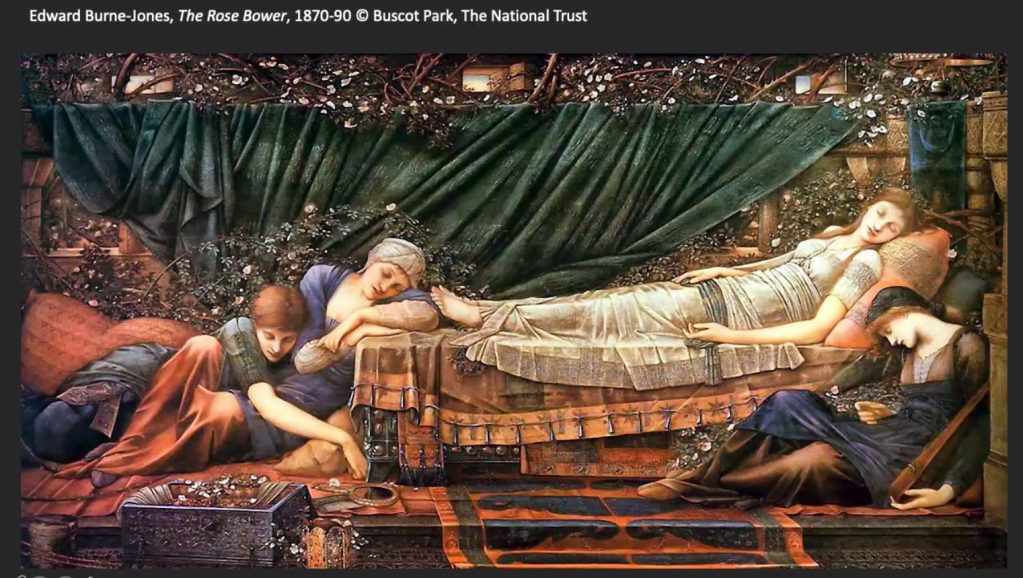

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, founded by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais and Dante Gabriel Rossetti (but later joined by a number of other artists) were also keen observers of the natural world, who were championed by the art critic John Ruskin. They studied nature attentively and recorded what they observed in minute detail. Some of the Pre-Raphaelites were fascinated by medieval culture and ultimately the group divided to follow two different directions. The Realists were led by Hunt and Millais, while the medievalists were led by Rossetti and his followers, Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris.

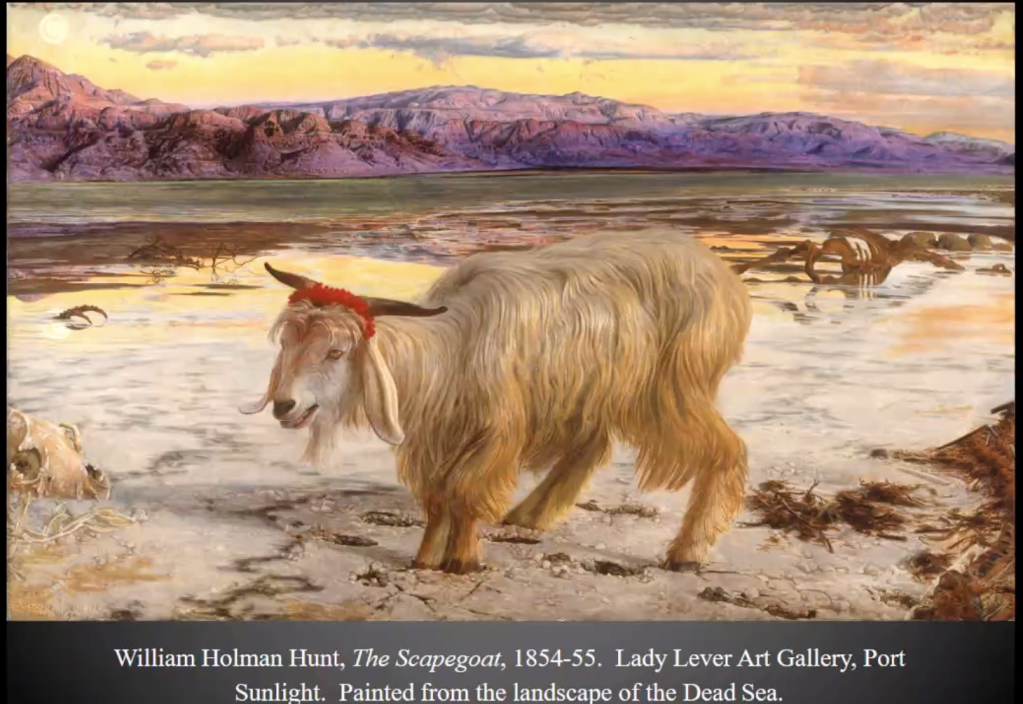

In the second half of this week’s session, Dr Jenny Graham explored the concept of representation through the ‘Realism’ of the Pre-Raphaelite painter William Holman Hunt, with a particular focus on his Holy Land pictures, which were explored in relation to empire, religion, travel and colonialism. Holman Hunt had a life-long interest in the Middle East. Jenny Graham told us that he tried to civilise other lands with his paintbrush in one hand and his bible in the other. The Scapegoat is an example of this.

Through quotes from his personal diaries and by close examination of his paintings we see that Holman Hunt was a product of his times, i.e. inherently racist, deeply influenced by the norms of the British Empire and colonialism.

Week 4: The Painters of Modern Life

The Painter of Modern Life is the title of an essay by Charles Baudelaire, who urged painters to break from historical narratives of the past and paint contemporary Paris and modern urban life. Baudelaire used the term ‘flaneur’ (meaning ‘stroller’ or ‘loafer’) to describe these observers of modern urban life. As such Baudelaire approved of Edouard Manet’s paintings which were considered shocking at the time.

Music in the Tuileries Gardens 1862, by Édouard Manet – National Gallery, London, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1784392

Manet blurred the lines between genders and social classes and broke a lot of the accepted rules of perspective and application of paint. Consider the tree trunk which almost splits his painting, Music in the Tuileries Gardens, in two, and the blue triangle of sky at the top of the painting. His handling of paint was loose and sketchy, finished yet unfinished, and his technique had a flattening effect, flattening space and figures. Manet’s paintings were refused by The Salon in Paris, but Napoleon III instituted the Salon des Refusés, where Manet exhibited instead. Even there his paintings, which were blatantly defiant, caused a scandal, particularly his nudes, which were of real people, not idealised; naked, not nude.

Le déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1863, by Édouard Manet – twELHYoc3ID_VA at Google Cultural Institute maximum zoom level, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21855901

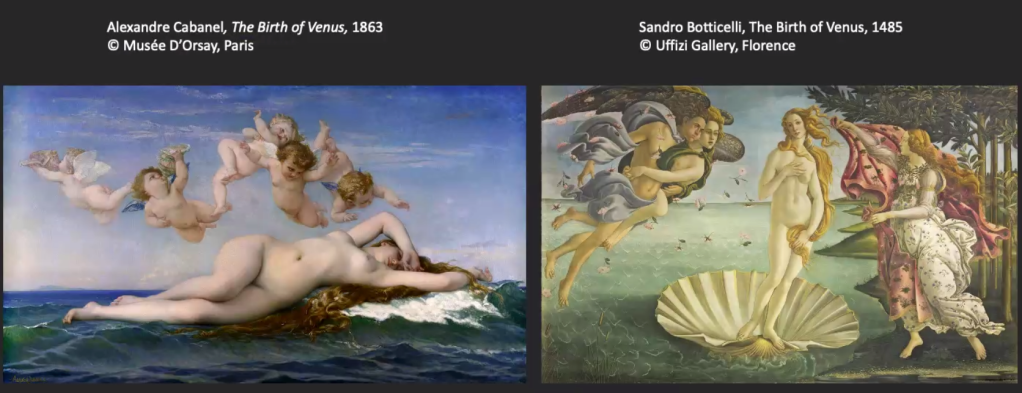

At the time, there was a large tradition of painting nudes in the standard drawn from classical art, in which the line and form were smooth and soft, with no distortions. Colours were muted with the figures painted in pale white, depicting virtue, and often painted as part of a narrative, a character in a story.

Historically the female nude had been painted by men for men, as exoticised ‘others’, but with the influence of the changing times, the re-organisation of neighbourhoods in Paris, the rise in employment and of the lower middle class, and the increasing development and influence of photography on painting, rules were being broken in many aspects of life, and the nude was toppled from its lofty pedestal. Developments in painting in the 19th century were shaped by shifting socio-cultural and political structures, which were manifested in challenges to a hierarchy of genres in painting as well as themes of identity, representation and performance. The iconic, sensual nude became a vehicle for provocation, experimentation and radical departures in painting.

Week 5: The Advent and Advance of Impressionism

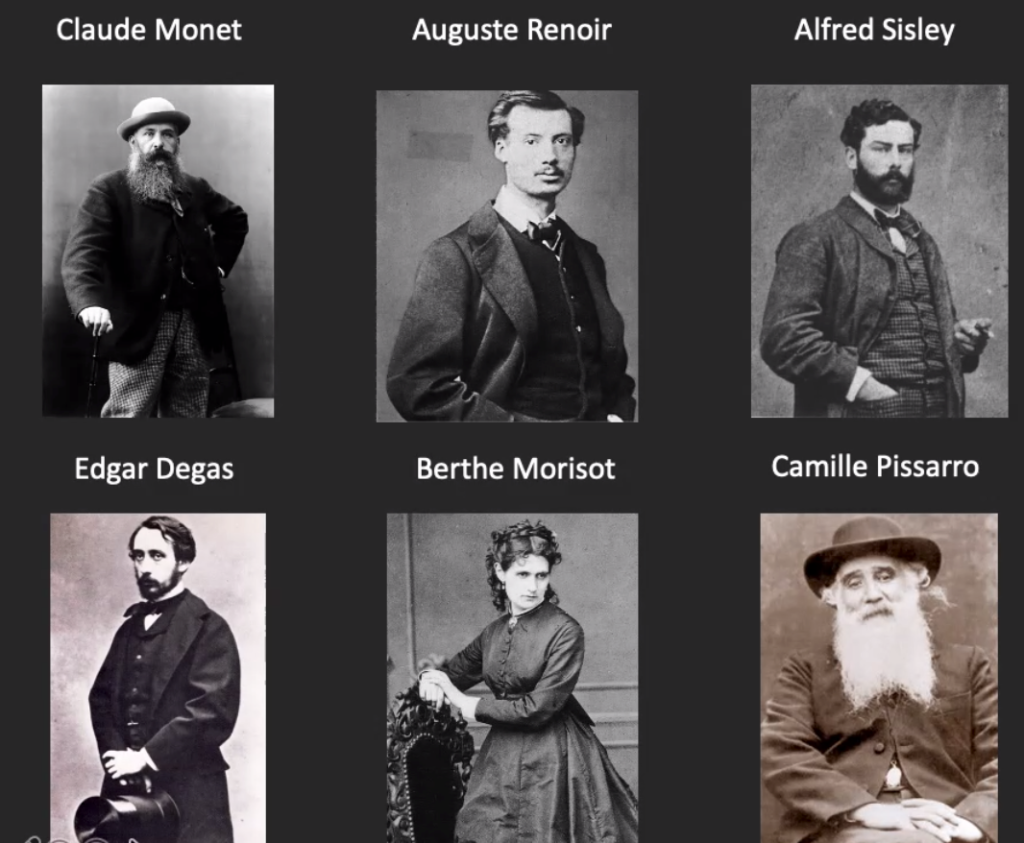

With their first independent exhibition in 1874 (not at The Salon, where they refused to exhibit) , Monet, Renoir, Sisley, Degas, Morisot and Pissarro became household names. There is something inspiring about their refusal to exhibit at The Salon. What courage of their convictions they must have had in the face of severe criticism of their work, which rejected the traditions of the time.

This group did not call themselves impressionists at the outset. The movement started with Monet’s painting bearing the title Impression.

A great variety of work was produced by the Impressionists. Manet was linked to this group, and a good friend of Monet’s, but wasn’t an impressionist and didn’t refuse to exhibit at The Salon. The Impressionists painted modern life and structures, for example, trains, railways, cities; strong and vulnerable women; and images of rural leisure. Bathing was also a popular subject at this time. See for example the work of Degas, Caillebotte and Eakins. The impressionists adopted a radical technique of short, broken, loose and sketchy brushstrokes, such that their works looked unfinished. The development of oil paints in screw top tubes and folding easels and stools, meant that they could, and did, work outdoors. They painted straight from the tubes, using unblended, bright colours, paying close attention to the effects of light. This was a time of opportunity and new freedoms for women, as we see in the work of Mary Cassatt and Berthe Morisot. Also, at this time, trade was re-established with Japan for the first time in 250 years, and the influence of Japanese design and pattern can be seen in the work of many artists in Europe, and in the work of James Abbott Whistler, who was considered the quintessential American impressionist.

In the second half of this week’s session Dr Jenny Graham focussed on Whistler’s paintings and the theme of ‘whiteness’, with reference to race, gender and the public display of art in London and Paris. For Whistler white is a philosophical, artistic and theoretical problem. He explores how white is not a single tone, but many tones with lots of intricate shadows, in his beautiful series of three Symphony in White paintings Unlike other Victorian artists of the time, Whistler was more interested in what paint can do, rather than the politics of the time, an approach that is known as ‘Art for art’s sake’. He wanted painting to be a sensory as well as a contextualised experience. His three Symphony in White paintings were considered shocking, not because they were experimental, but because the subject (Whistler’s mistress) looks like a fallen woman, a girl who has lost her virginity.

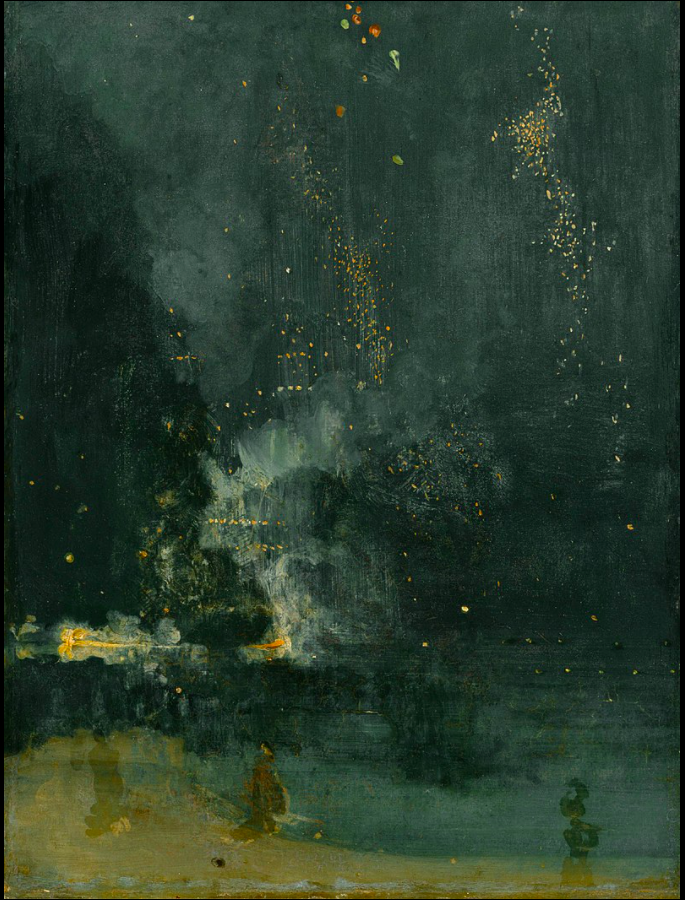

But it was Whistler’s painting Nocturne in Black and Gold. The Falling Rocket, which caused the most scandal, inviting severe criticism from John Ruskin, who thought Whistler had asked too much money for a painting in which there was no evidence of any work. Ruskin thought labour should go into a work of art. Whistler sued Ruskin for libel, and won, but ultimately the trial bankrupted him. Dr. Caroline Ikin talks about their argument on YouTube https://youtu.be/dLmWqkggaiM

Week 6: The Crisis of Impressionism and Beginning of a New Century

The Impressionists held eight independent exhibitions and with every passing year the artists became more divergent from the characteristics which initially bound them together. The eighth exhibition in 1886 included artists who would later be called the Post-Impressionists. Once again many, many slides were shown this week, but the focus paintings were:

- Georges Seurat, Bathers at Asnières, 1884

This is painted in Pointillist style, a Post-Impressionist technique developed by Seurat. Paul Signac also helped to develop this style, which explored the use of complementary colours and gave the paintings a shimmering effect. Pissarro also experimented with Pointillism, but after a few years returned to Impressionism. See, for example, his painting Late Afternoon in our Meadow.

- Paul Gauguin, Faa Iheihe, 1898. Tate Gallery.

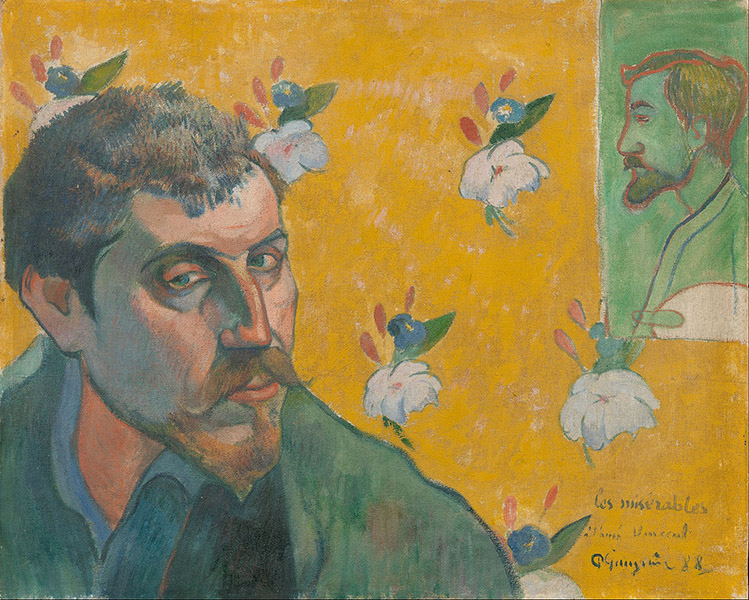

Gauguin was influenced by the work of Seurat and Signac. He too moved away from Impressionism. Gauguin is best known for his primitive, non-Western art; its simplicity, sincerity and expressive power, and also for his relationship with Van Gogh for whom he painted this self-portrait.

Gauguin’s style of Post-Impressionism has been termed Cloisonnism, a technique in which areas of bold, flat colour are separated by strong, dark contours. Gauguin also used the term Synthetism to describe his work.

- Vincent van Gogh, Sunflowers, 1888

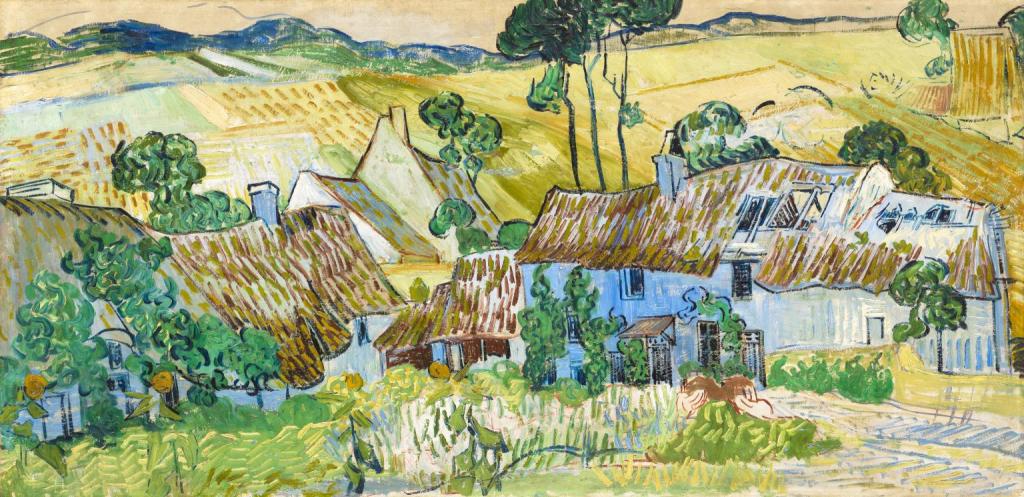

The second half of this week’s session was devoted to Van Gogh and Cézanne. Some things I didn’t previously know about Vincent (as he liked to be called) are that he was largely self-taught, a prolific painter, producing 900 paintings and 1000 works on paper between 1880 and 1890. He loved the work of Millais and copied his paintings. He was deeply religious, and his famous sunflower paintings are evocative for Christians, for just as the sunflowers turn to follow the sun, so do Christians turn to follow Christ. I knew that his mental health was fragile and that he cut off his ear, but I didn’t know that he took his own life in 1890, shooting himself in the chest. This was his final, but unfinished painting, before he died. Farms near Auvers, 1890.

- Paul Cézanne, Bathers (Les Grandes Baigneuses), 1894-1905

This module ended with a focus on Cézanne, who is considered the founder of 20th century modernism. Cézanne was a Neo-impressionist. He used subtle gradations in colour to build form and create three-dimensional space, and anticipated cubism with geometric shapes. Cézanne was interested in how the human eye sees and how our minds process different perspectives.

The final Module 7 in this online course, Stories of Art. A Modular Introduction to Art History starts on Wednesday 14th July, and will cover 1900-2021. I expect it to be just as packed with content.